Events are not evolving as people on the FOMC envisioned last year, and the Fed is not currently achieving its goals. A slow and plodding approach isn’t good enough, and it’s time to change course. What’s going wrong, and what’s the fix?

First, how did we get here? In August 2020 the FOMC unveiled a new “Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Policy Strategy.” For our purposes there are three important elements in that Statement. The first is:

“Owing in part to the proximity of interest rates to the effective lower bound [because the neutral interest rate is low], the Committee judges that downward risks to employment and inflation have increased.”

So, the key problem the Fed was focused on was the low real real rate of interest. Low real interest rates imply that the average overnight nominal interest rate consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target must be lower, implying that, given typical stabilization policy, the Fed will encounter the zero lower bound (or some effective lower bound) on nominal interest rates on a more frequent basis. The FOMC thinks that zero-lower-bound encounters tend to cause low inflation and low real GDP growth — a notion supported by the New Keynesian academic literature on sticky-price zero-lower-bound economics.

So, this is our first problem. A key issue the FOMC anticipated dealing with — inflation below target — is not the major problem that the FOMC needs to deal with now, which is inflation well above its 2% target.

Second, the Statement says:

“…the Committee’s policy decisions must be informed by assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its maximum level, recognizing that such assessments are necessarily uncertain and subject to revision. The Committee considers a wide range of indicators in making these assessments.”

So, this says is that maximum employment is a goal, but how we measure it is something we can make up as we go along. Third,

“…the Committee seeks to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time, and therefore judges that, following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.”

This is a quasi-average-inflation-targeting approach which, in contrast to straightforward inflation targeting (what the Bank of Canada does, for example), takes past misses of the inflation target seriously, and attempts to make up for those misses. But, the Statement leaves a lot out. How much of the past will the FOMC consider when it thinks about making up for past misses? How long is the future makeup period supposed to be? And, perhaps most importantly, given current conditions, how come the FOMC did not specify what would happen if there were inflation target misses on the high side?

So what’s going on in the data? Let’s look at prices first.

Here, red is the headline CPI, blue is the PCE deflator (what the FOMC claims to care about), and green is a 2% trend from January 2020. Everything is normalized to 100 in January 2020. Recall that the FOMC’s Statement of Goals says that, if inflation runs below target, then the Fed is supposed to target inflation “moderately” above target. In the chart, average inflation was below target until March of this year, but by March, the Fed had made up for the undershooting in 2020. In fact, average PCE inflation has been 5.8% per year since February of this year, and will come in at 5.3% year-over-year in December 2021 if the inflation average is the same for the remaining 3 months of the year as in the preceeding 9. So, this is hardly “moderate,” I think, and the undershooting was made up long ago, if we take our base period as January 2020. It appears that the Fed is willing to tolerate inflation well above target, in a manner inconsistent with what was written down in the FOMC’s goals statement.

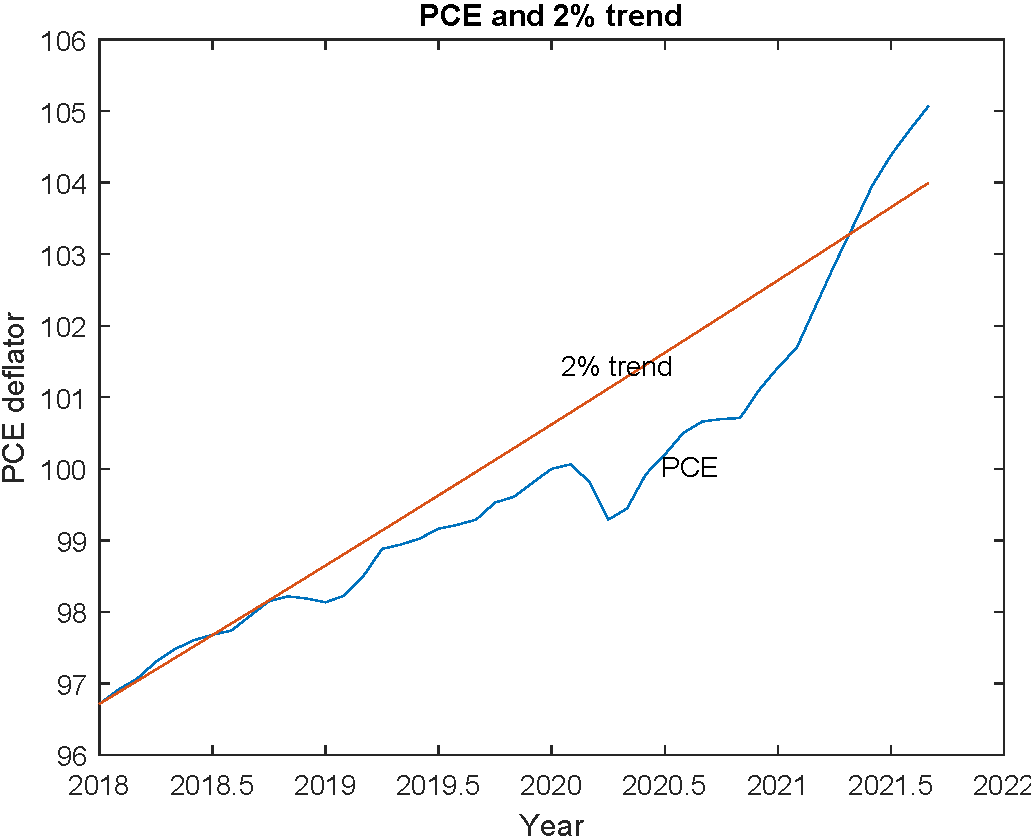

But what if we use an earlier base period? This is what we get with a base period set at January 2018.

So, note here that the Fed has more than made up for inflation target undershooting going back almost 4 years. But the Fed’s policy rate (the interest rate on reserves) is still at 0.15%, and the FOMC has just committed to a start in reducing the rate of its asset purchases — a process that will not end until the middle of 2022. Given the ideas of FOMC members about inflation control, how do they justify emergency settings for policy instruments given their own Statement of goals and what we’re seeing in the inflation data?

But maybe there’s something in FOMC statements that we can use to make sense of this. From the November 3 statement:

“The Committee seeks to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run. With inflation having run persistently below this longer-run goal, the Committee will aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time so that inflation averages 2 percent over time and longer‑term inflation expectations remain well anchored at 2 percent.”

But, that’s not right. As we’ve shown, inflation has not been running persistently below 2%, even if we go back almost 4 years. However, maybe the FOMC is worried about the second part of its mandate — the maximum employment goal. After all, the November 3 FOMC statement also says:

“The Committee expects to maintain an accommodative stance of monetary policy until these outcomes [maximum employment and inflation at 2%] are achieved.”

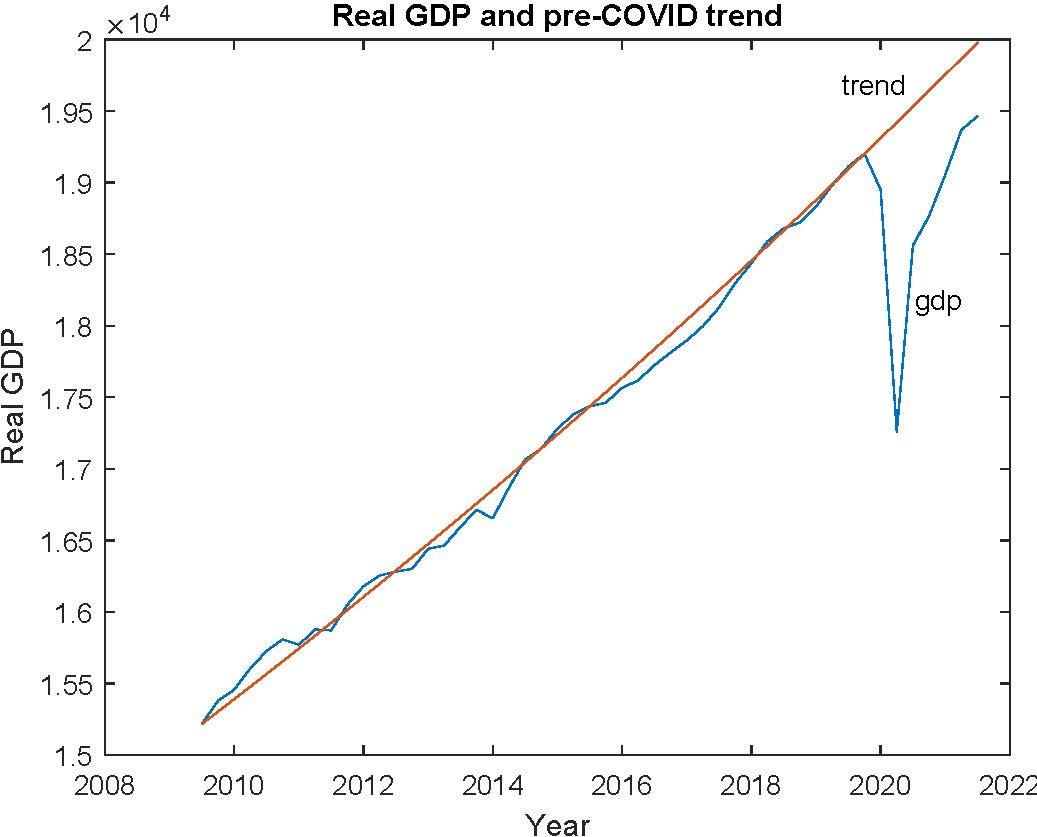

So, how are we doing on the labor market front? First, real GDP has made a rapid recovery, relative to previous recessions.

Though higher than it was in 2019Q4, real GDP is still 2.8% below the post-financial crisis trend. And in the labor market, the labor force participation rate and employment/population ratio are very low, relative to early 2020.

So, those indicators might signal a shortfall relative to maximum employment. However, here’s what we see when we look at other labor market indicators:

The unemployment rate is currently at 4.6%, which is the same is August 2006 or in February 2017, neither of which we would characterize as bad times. More strikingly, the job openings rate is at an all-time high (at least since we’ve been measuring it). For emphasis, here’s a standard measure of labor market tightness, the ratio of job openings to unemployment:

That’s also at an all-time high. So are we at maximum employment? We could argue yes. Why labor force participation and the employment-population ratio are low is something of a puzzle, particularly since we don’t observe this in Canada, where most labor market indicators are close to where they were in early 2020. But one could make a case that low labor force participation is a choice — maybe primarily due to the pandemic. There are plenty of jobs available, and this economy is more or less producing all it can, given the circumstances.

So, unfortunately, this episode illustrates the limits of forward guidance — at least forward guidance that commits the central bank to future actions without anyone thinking through all the possible future contingencies. The FOMC seems implicitly committed to a policy of tapering — reducing asset purchases — before there are any increases in the overnight interest rate target. That just creates foot-dragging into mid-2022, when action now is appropriate, given the FOMC’s own principles, as written down in its Goals Statement and FOMC meeting statements.

If you’ve read other things I’ve written, for example this piece in the St. Louis Fed Review (and there’s more where that came from), then you’ll know that I think the best way to do inflation control is in terms of Fisherian logic. High nominal interest rates for a long time imply high inflation, and low nominal interest rates for a long time imply low inflation. Just ask people who live in Japan. If a central bank is persistently undershooting its inflation target, it needs to find excuses to raise its overnight nominal interest target.

So, according to this logic, shouldn’t the Fed just hold tight with the policy rate at 0.15% and wait for inflation to come down? No, because inflation control is about bringing the central bank’s overnight nominal interest rate back to a level consistent with its long-run inflation target, after any period where the policy rate has been moved around for stabilization policy reasons. For example, the Fed’s response to the pandemic had little to do with inflation control. The Fed thought, correctly, that emergency action was necessary in early 2020, and reduced its policy rate essentially to zero (I’ll leave aside QE, which I think is ineffective). But once that was done, the game is to find excuses to move toward “normal,” which in this case could be a policy rate of about 2%, supposing the long-run real interest rate is about 0%. That is, interest rate hikes should take place in the context of good news. If you’re looking at the right things currently, the real economy is giving off good news. The inflation data is bad news, in a sense, but good news in terms of pressure to tighten.

I think it’s still likely that the burst of inflation we’re seeing is temporary — in fact, that we’ll be seeing inflation below the 2% target next year, in year-over-year terms, if policy settings remain where they are. As I saw Ricardo Reis discussing on Twitter recently, it doesn’t matter much what your theory of inflation is right now. You could be a hard-core Phillips curve type or even an old school monetarist and think that it’s time to tighten. The Fed should get on with it.

I did not understand this, sorry: "I think it’s still likely that the burst of inflation we’re seeing is temporary — in fact, that we’ll be seeing inflation below the 2% target next year, in year-over-year terms, if policy settings remain where they are."