This piece follows from my previous two-part post: “High Inflation: Where Did It Come From, Part I and Part II.” Basically, that was an attempt to debunk some typical narratives about the sources of our current high inflation numbers, and to come up with a reasonable story that allows us to sort out monetary policy for the immediate future. The conclusion is that pandemic inflation is due to deferred consumption, and a symptom of that was a surge in holdings of transactions balances. If we take that symptom as critical, then its important that the surge is going away. Thus the resulting inflation surge is indeed temporary, and it may be unfortunate that the Fed has changed its mind and decided its not.

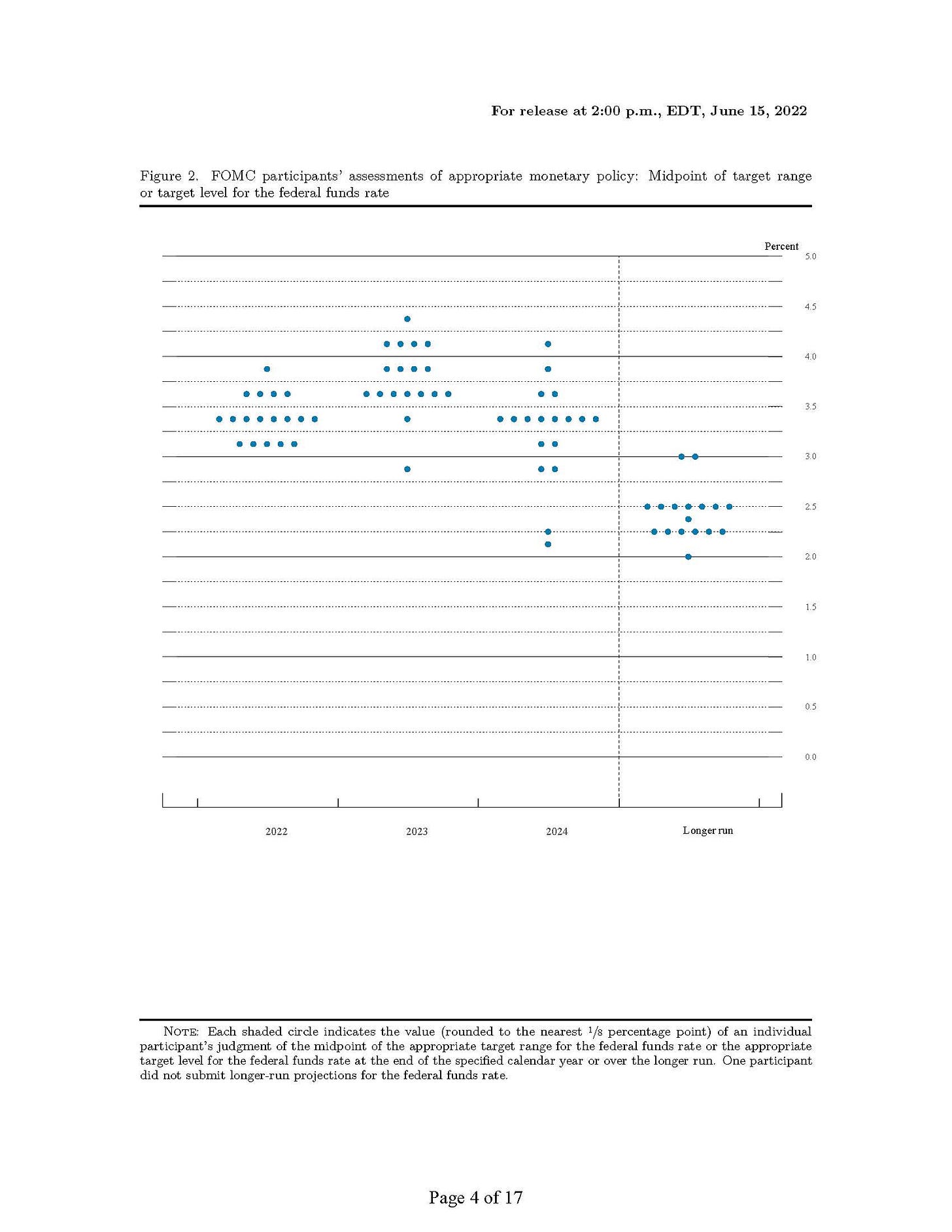

So, how does the Fed want to control inflation? We know what the FOMC has done thus far. In the last three meetings, the Fed has been unusually aggressive, increasing the overnight policy rate target by 150 basis points, with the fed funds rate currently at 1.6%, where it was before the pandemic. In its last projections, FOMC members’ dot plot looks like this:

Chart 1

To the far right in Chart 1, we can take the dots to represent committee members’ estimates of the “neutral nominal interest rate,” or the long-run overnight nominal interest rate consistent with 2% inflation, given the absence of macroeconomic shocks for some time, or some such. The median is 2.5%, which comes from a median estimate by the committee members of a long-run real interest rate (or “natural real interest rate”) of 0.5%. Then, using Fisherian logic, add 2% (the inflation target) to get 2.5%. So, the median view on the committee is that, to sustain 2% inflation in the long run, an overnight nominal rate of 2.5% is appropriate.

But you can see that the committee thinks that increasing the overnight interest rate target by another 90 basis points to 2.5% isn’t sufficient to control inflation. The median view as that there should be an overshoot of the neutral nominal rate. The median FOMC person thinks the policy rate should be about 3.4% at the end of this year, and 3.75% at the end of 2023. If you look at the inflation projections included with the dot plots, the FOMC is expecting that inflation will still be above 2% at the end of 2024, with the policy rate above 2.5%.

There are many people that I’ve talked to, and people whose prognostications I’ve read, who think that the FOMC’s projected policy is not aggressive enough. I’ll take Larry Summers’s piece in the Washington Post as representative of this view. Summers says:

…it [the FOMC] is not raising real rates above the neutral level. On the Fed’s forecasts, real rates — interest rates adjusted for inflation — will be negative and well below their neutral level for this year and next. On market forecasts, real rates will not reach zero, let alone their neutral level, within the next decade.

Basically, Summers thinks the real interest rate needs to be sufficiently high to bring inflation under control.

When Summers says “interest rates adjusted for inflation,” I’m interpreting this as the ex-post real interest rate, that is the current nominal interest rate minus the actual rate of inflation. Here’s what that looks like:

Chart 2

In terms of how Summers thinks about the world, that’s very alarming. He thinks low real interest rates cause high spending, which makes unemployment low, which makes inflation high, via a Phillips curve (PC) effect. So, according to this view, real interest rates cause inflation, which is consistent with a standard narrative about what caused high inflation in the 1970s. That is, according to that view, the low real rates you see following the 1974-75 recession in Chart 2 caused the high inflation that Paul Volcker had to deal with during his two terms at the Fed (1979-1987).

Summers’s logic is basically the same as what’s behind the Taylor rule, specified in its original form as:

(1) R = r* + i* + a(i - i*) + by,

Here, R is the target for the overnight nominal interest rate, r* is the natural real interest rate, i* is the target rate of inflation, i is the actual rate of inflation, and y is the output gap, i.e. some measure of slack in the economy. Finally a and b are parameters with a > 1 (the Taylor principle) and b > 0. For our purposes, set b = 0, supposing we’ve got a policymaker with their mind set on inflation control. Then, if r* = 0.5, as the FOMC seems to think, and i* = 2, then the Taylor rule tells us the current target for the overnight nominal interest rate should be somewhere north of 7.3%. Further, note that the Taylor rule implies that the ex-post real interest rate, when b = 0, from (1), should be

(2) R - i = r* + i* + (a - 1)(i - i*)

So, the Taylor rule dictates a nominal policy rate above the neutral rate, r* + i*, so long as inflation is above target, which I think is what Larry Summers wants the Fed to do.

It’s clear from (1) that when the central bank is achieving its goals, then the overnight nominal rate will be equal to the neutral nominal rate, so if the central bank knows r* (an important issue, but suppose they get it right) then the Taylor rule is at least consistent with a long run in which, if the central bank achieves its goals, its policy rate is equal to the neutral rate. But how do we know that the Taylor rule takes us to Nirvana?

Typically, in standard monetary models we like to play with, including those with sticky prices, the Taylor rule generally doesn’t take us to Nirvana. There are Taylor rule perils, as Benhabib and coauthors originally pointed out. Basically, in models where we can work out the global inflation dynamics (not linearized New Keynesian models, for example) a Taylor rule with the Taylor principle produces multiple equilibria, with many of those converging to a zero-lower-bound steady state with zero nominal interest rates and low inflation. That happens because Fisher effects are more important than typically realized, in standard monetary models. That is, an aggressive central banker, seeing inflation below target, lowers the target nominal interest rate, which further lowers the inflation rate, which further lowers the nominal interest rate target, etc., until the nominal interest rate goes to its lower bound. And there it stays, so long as the central banker adheres to the Taylor rule.

But what happens when inflation is above target? In some models, I think inflation above target can’t be sustained, but in a baseline case with money neutrality (say an endowment economy with cash in advance), the Taylor rule will sustain an equilibrium in which inflation increases forever. Basically, higher nominal interest rates effectively accommodate the higher inflation — supported of course by open market operations. So, Summers, and many others like him, think that low real interest rates cause high inflation, but typical dynamic models say that, if you follow policies based on that idea, high nominal interest rates will act to propel high inflation.

For example, going back to 1970s inflation:

Chart 3

In Chart 3, the blue line is the fed funds rate, red is the PCE inflation rate, and green is the ex post real interest rate. So, in the chart, is the low real interest rate causing the inflation rate to go up, or is the nominal interest rate going up, thus accommodating the high inflation? Note in particular that there are times when the increase in the fed funds rate leads the increase in the inflation rate.

The idea that Fisher effects are important for monetary policy, sometimes called Neo-Fisherism, isn’t just part of mainstream monetary theory, there’s empirical work on this too. In particular, work by Martin Uribe and Azevedo, Ritto, and Teles argues that the data support the notion that temporary increases in the nominal interest rate reduce inflation, but persistent increases result in inflation going up. And the long run where the Fisher effect dominates comes much sooner than you might think.

John Cochrane thinks that FOMC members are effectively Neo-Fisherites (though maybe they don’t know it). They’re not like Larry Summers, in that they don’t want to adhere to an aggressive Taylor rule, thinking that high inflation will pretty much go away on its own. Though you’ll notice that the June FOMC dot plots are more aggressive than the March ones were, so maybe the FOMC is moving in a Summers direction. So, I see at least three possible outcomes here:

Inflation starts coming down of its own accord sooner than most people expect, the FOMC backs off some, and there’s a smooth path to R = 2.5% and 2% inflation with no recession (ha ha).

Inflation is more persistent than I think it will be, the Fed gets more aggressive, the high nominal interest rates accommodate the high inflation, and then we really have a serious inflation problem, but no recession.

Inflation is more persistent than I think it will be, the Fed gets more aggressive, we have a recession, the Fed reduces its nominal interest rate target and, by Fisherian logic, inflation comes down. The Fed pats itself on the back, Jay Powell is a big hero, starts smoking cigars like Paul Volcker, and Larry Summers is surprised that we didn’t need 5 years of 5% unemployment to bring inflation down.

I am a new reader trying to get sorted on economics at the macro level after an intro/intermediate sequence.

Thank you.