Should We Be Happy with the Bank of Canada?

Given Wednesday’s monetary policy decision by the BoC, and the publication of April’s Monetary Policy Report, it’s a useful time to take stock of what the BoC is up to.

In some ways, the BoC is as transparent as any central bank but, particularly relative to the Fed, we know little about what goes on in the discussion that leads up to a meeting of the Governing Council, where decisions are made 8 times per year. The Governing Council (the Governor, Senior Deputy Governor, and four Deputy Governors) meets in secret, no vote is taken on the decision, and the Governor can basically do what they want. So, if something goes wrong you know who to blame - the guy at the top of the page, Governor Tiff Macklem.

Taking into account what we’ve had to deal with since a year ago, the Canadian economy is in good shape. This is from the April Monetary Policy Report:

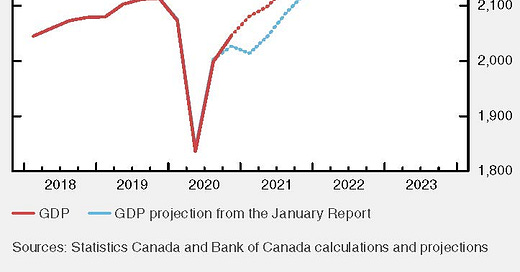

Fourth quarter real GDP was an upside surprise, which caused the BoC to revise up its forecast, as reported in its previous Monetary Policy Report. That upward revision is consistent with what private forecasters are saying, so there is considerably more optimism about future macroeconomic activity than was the case a couple of months ago. Eyeballing the chart, the BoC thinks that real GDP will be back on trend in the latter half of 2022. Keep that time horizon in mind, as that will be important for how the Bank has framed its forward guidance. The monthly data strengthens the case for optimism. Here’s employment data from the Monetary Policy Report:

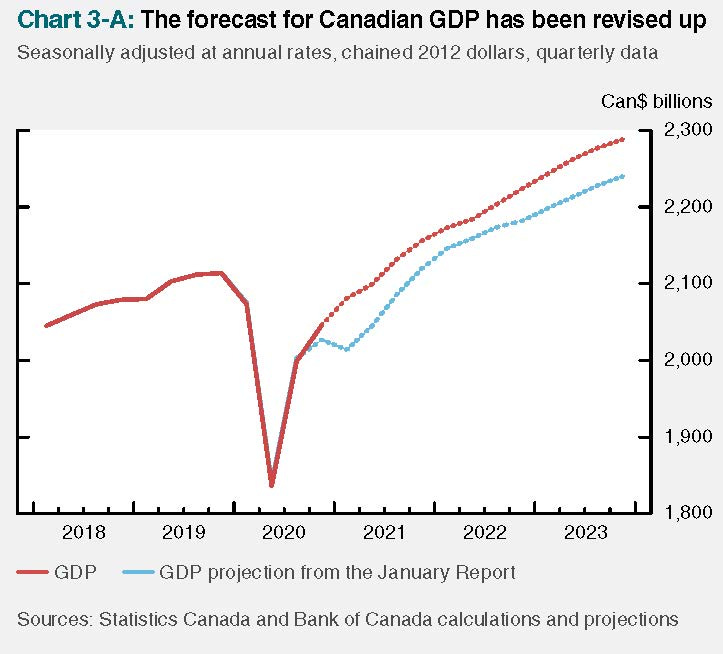

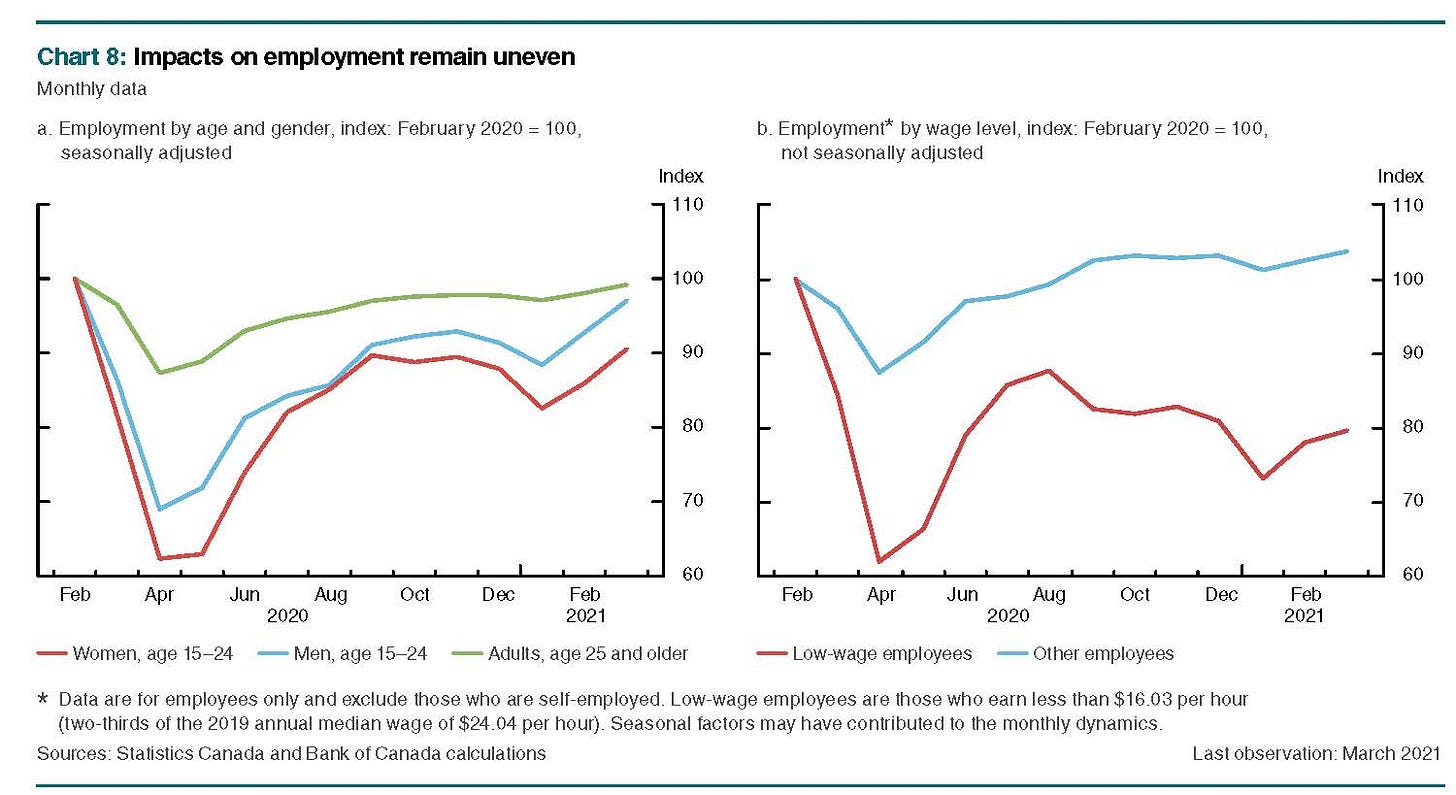

There’s still dispersion in employment across groups, for example employment of low-wage workers remains low due to continuing COVID restrictions, but employment growth is generally good and, again, has surprised on the upside. And of course, particularly since the BoC has a headline CPI inflation target of 2% (in a 1%-3% range), we have to pay attention to inflation. Again, from the Monetary Policy Report:

Just prior to the pandemic, inflation had been pretty much on target. As in the US, inflation fell in Spring 2020, with attendant measurement issues that tended to temporarily bias inflation down. Measured inflation is currently at the bottom of the 1% to 3% range (though I see that the March number came in at 2.2%), but we’re about to move into a period where we’re calculating year-over-year inflation from a low base in Spring 2020, and we’re also seeing large increases in commodity prices. As a result inflation should be temporarily high - perhaps toward the top of the 1% to 3% range - until the fall. That’s the BoC’s take anyway, and I agree with it. Where we may disagree is with respect to what might come later.

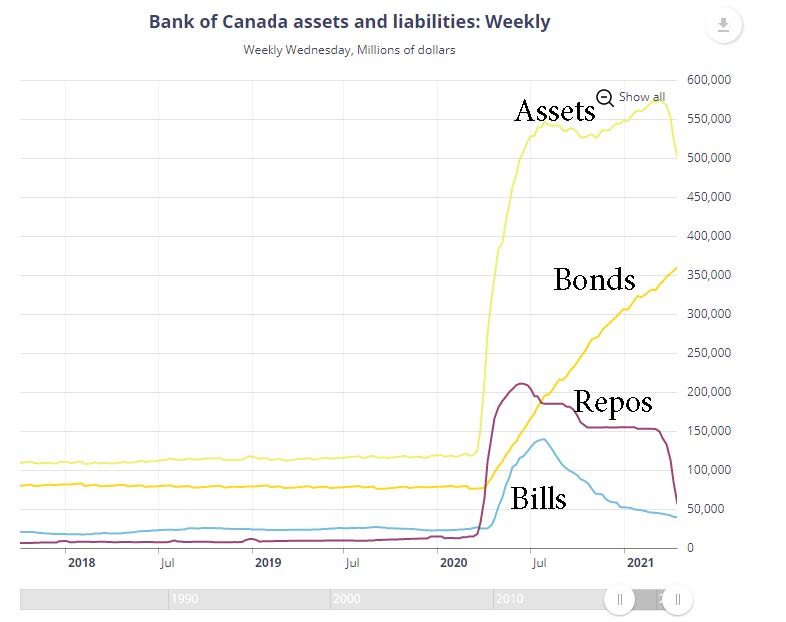

Unconventional monetary policy is new to the BoC, but they have been fairly aggressive about it since March 2020.

QE in Canada has consisted primarily of purchases of long-maturity Government of Canada bonds, initially at a pace of $5 billion a week, subsequently reduced to $4 billion per week (seemingly because this was having disruptive effects in financial markets), and then to $3 billion per week in the policy decision yesterday. The latter appears to be the beginning of a tapering-off in bond purchases, though in the press conference Macklim wouldn’t confirm that.

An interesting part of the intervention, evident in the last chart, was substantial repo market intervention (some was term repos), on the lending side, presumably intended as a broad-based lending operation, though BoC officials never said much about it, focusing on QE. But note that, since the middle of last year, there has not been much change in the size of the Bank’s balance sheet, as net bond purchases have been roughly matched by a declines in repo lending, and in the Bank’s holdings of Government of Canada T-bills. In the last few weeks, though, balance sheet size has come down. On net, the average maturity of the Bank’s asset portfolio has increased substantially.

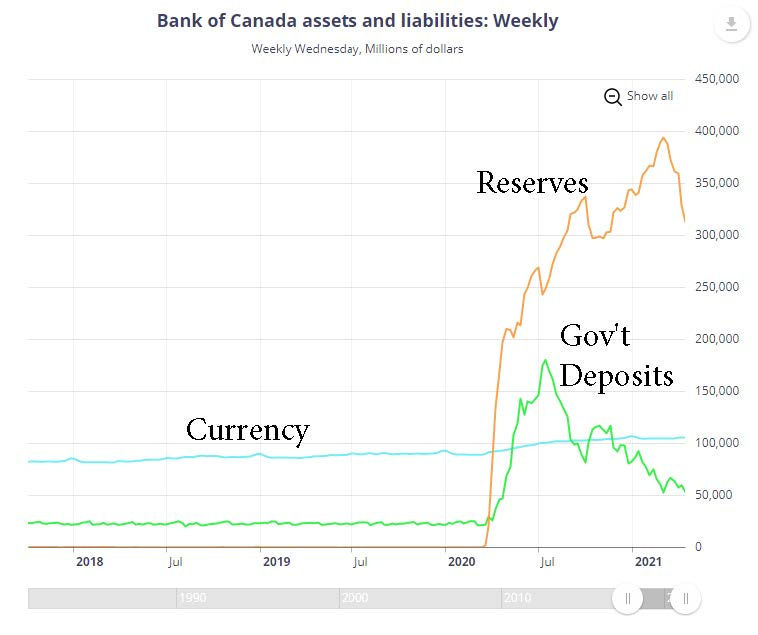

On the liabilities side of the balance sheet:

In this chart, the large-scale asset purchases are reflected in increases in liabilities, primarily reserves (deposits of financial institutions with the BoC), and government deposits (basically the government’s chequing account with the BoC). Presumably the federal government thought it important to have a buffer of deposits with the Bank during the pandemic. Those balances have fallen over time, though they’re not back to normal levels yet. Note that, everything else held constant, a reduction in government deposits will increase reserves one-for-one, which in part explains why reserves have continued to increase since mid-2020. However, in recent weeks, the declines in the Bank’s short-term assets have reduced reserves as well.

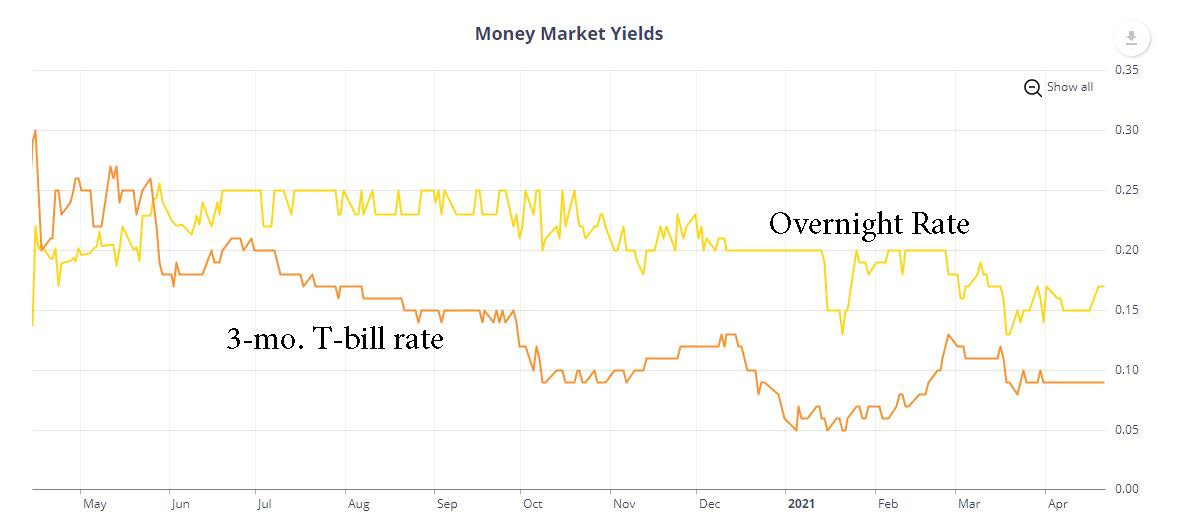

To get a full picture, so we can evaluate the effects of QE, we’ll look at interest rates. Short-term rates first:

In March of 2020, the BoC reduced its target for the overnight rate to 0.25%, where it has been since. Given the large-scale asset purchases, the Bank has been running a floor system. That is, in theory the interest rate on reserves (BoC deposits), at 0.25%, should determine the overnight rate, through arbitrage in overnight credit markets. But you can see that has not happened. Since late last year, the gap between the interest rate on overnight central bank balances and the overnight rate has increased to about 10 basis points, as shown in the chart. And the margin between the interest rate on reserves and the three-month T-bill rate is even larger, at close to 20 basis points at times. The Fed’s floor system, in operation since the financial crisis, is notorious for friction, and lack of arbitrage, but one might have thought that wasn’t the case in Canada, given the BoC’s prior experience with a floor system in the period from Spring 2009 to Spring 2010.

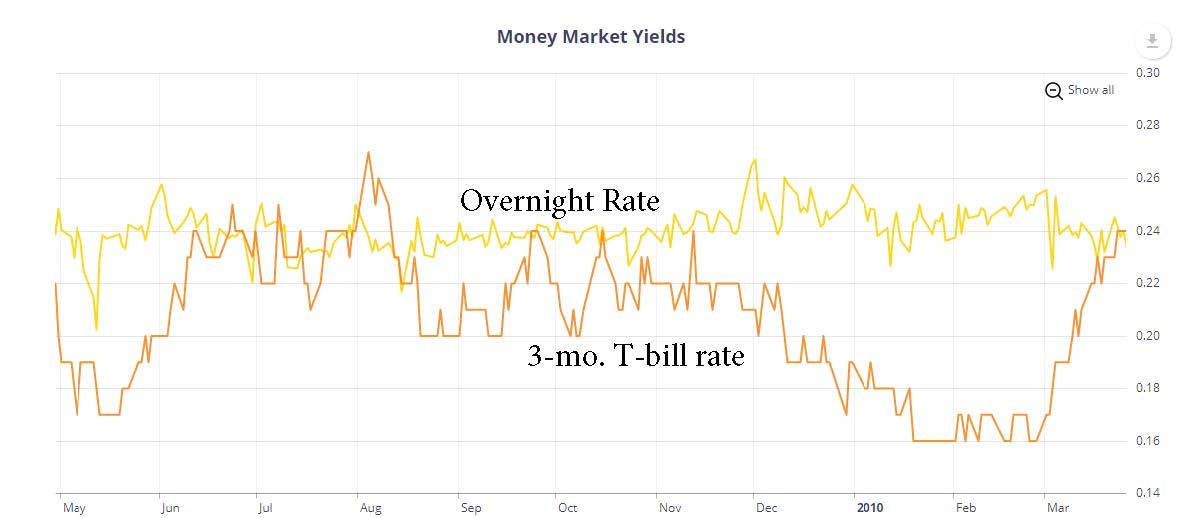

This chart shows the same interest rates for the earlier period. Typically, the overnight rate was closer to the interest rate on reserves during that period than is the case now. The overnight rate was at most one or two basis points on either side of the interest rate on reserves. And the 3-month T-bill rate was usually lower than the overnight rate, but at most only 10 basis points lower than the interest rate on reserves.

A standard narrative that you hear in US monetary policy circles is that floor-system deviations of the overnight rate from the interest rate on reserves will go away with sufficient reserves in the system. But here, the interest rate differentials have become larger as the size of the BoC’s balance sheet has increased, suggesting that large-scale asset purchases actually make overnight markets less efficient. How could that happen? Basically, the Bank is taking good collateral (government debt) out of financial markets, and replacing it with a less-useful asset, Bank of Canada deposits. Note in particular that financial institutions require a premium of up to 20 basis points to hold reserves rather than Treasury bills. Further, if the BoC thinks that their control over short-term interest rates could be better under a floor system, they should think again.

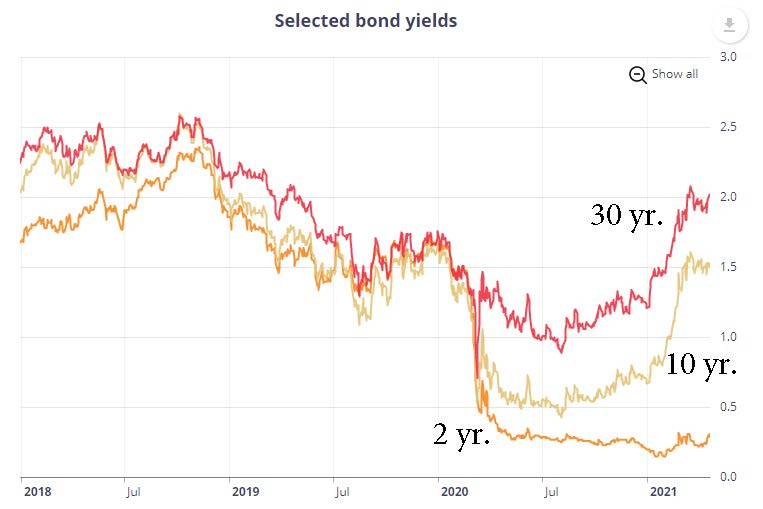

Let’s turn to long bond yields:

As in the U.S., there were sharp declines in bond yields with the onset of the pandemic and the drop in the policy rate, but in the figure the 30-year and 10-year bond yields have increased about 100 basis points from the middle of last year. Indeed, these bond yields are more or less back where they were before the pandemic. Unless you want to make the case that the inflation premia implicit in current bond yields are higher than in January 2020, say, it’s hard to see how QE did anything. The primary purpose of QE, as BoC officials explain it, is to reduce long bond yields. This is supposed to be “stimulus,” a word that Macklem used frequently in his Wednesday press conference to describe the Bank’s QE program does.

So, to me, the QE program seems a problematic component of the Bank’s policy. The world’s central bankers continue to defend QE as an effective policy, but there’s little or no evidence that it helps in terms of a central bank’s ultimate goals, and it could do harm to the functioning of overnight credit markets. Given the potential issues with QE, and the experimental nature of the program in a Canadian context, you might expect a greater effort on the part of BoC officials to explain how they think it should work, and to provide evidence that it is, in fact, working. Here’s what the Monetary Policy Report says:

“The cumulative stock, the flow and the composition of quantitative easing (QE) purchases continue to put downward pressure on borrowing rates, supporting economic activity. QE also reinforces monetary stimulus provided by the Bank’s forward guidance. This guidance has committed to holding the policy interest rate at the effective lower bound until economic slack is absorbed, so the inflation target is sustainably achieved.”

Here, I was hoping for some information on exactly how QE should work, if at all, and what characteristics of the central bank’s balance sheet - the size of the balance sheet, the first derivative of the size of the balance sheet, the maturity of asset purchases, what’s happening on the liabilities side - are going to matter for the effects of large-scale asset purchases. The above statement just says that anything could matter, and there’s no explanation, as far as I can tell, of how or why. In the press conference, Macklem just repeated what’s in the Monetary Policy Report.

The above statement links QE to the BoC’s forward guidance, so we should look at that. This is from the last paragraph of Wednesday’s press release, and I’ve included the last sentence of the previous paragraph.

“…As slack is absorbed, inflation should return to 2 per cent on a sustained basis some time in the second half of 2022. "

“Even as economic prospects improve, the Governing Council judges that there is still considerable excess capacity, and the recovery continues to require extraordinary monetary policy support. We remain committed to holding the policy interest rate at the effective lower bound until economic slack is absorbed so that the 2 percent inflation target is sustainably achieved. Based on the Bank’s latest projection, this is now expected to happen some time in the second half of 2022. The Bank is continuing its QE program to reinforce this commitment and keep interest rates low across the yield curve. Decisions regarding further adjustments to the pace of net purchases will be guided by Governing Council’s ongoing assessment of the strength and durability of the recovery. We will continue to provide the appropriate degree of monetary policy stimulus to support the recovery and achieve the inflation objective.”

At first glance, it’s hard to tell whether this is state-based or calendar-based forward guidance. State based says: “we will do x if we see y.” Calendar based says: “we will do x after z months have passed.” At the press conference, Macklem insisted that the guidance was “outcome-based,” which is the former. But based on what state or outcome? Saying the BoC will keep the policy rate at 0.25% until “economic slack is absorbed,” isn’t much help, as we can’t observe economic slack. Further, Macklem wouldn’t be pinned down in the press conference as to what slack measures he might be looking at - a wide, non-specific array, apparently. But I think you can infer what he’s talking about from the first chart. Late 2022 is when the Bank’s forecast for real GDP catches up to the post-financial crisis trend, extrapolated from fourth quarter 2019. And they’re hoping that inflation is on track in late 2022, as that’s when they’ll start to tighten. Why couldn’t the Governor just say that, and keep it simple?

Here are some issues with the policy, and things that could make life difficult for the Governing Council, and the Governor in particular:

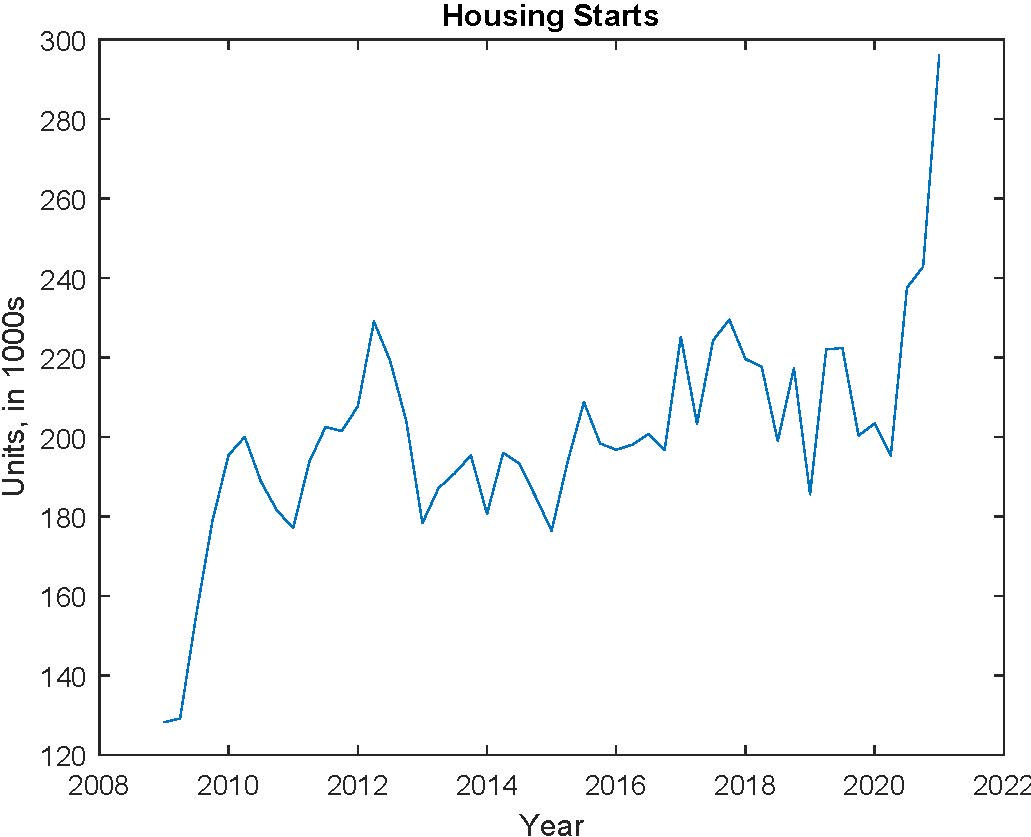

The BoC claims it is using QE to keep interest rates “low across the yield curve,” to provide stimulus. Presumably, in good part, they want to stimulate the housing market with low mortgage interest rates. But the housing market is booming, and apparently in no need of stimulus. Here’s the latest data on housing starts:

I don’t think this recovery will look typical. Some sectors - including housing - are already doing well, and the ones that are currently doing badly will come back in a hurry once more people are vaccinated and restrictions are lifted. The caveat is that there will be parts of the world that will be doing badly for some time. But the BoC could be surprised again on the upside, moving the reckoning date forward from late 2022 to something more like early 2022.

The Fed seems intent on staying at the zero lower bound into 2024, so carrying out the BoC’s forward guidance likely implies a significant departure from US monetary policy.

The longer the BoC keeps the policy rate low, the greater the risk of Japanese syndrome - a low policy rate and low inflation, indefinitely. For example, what if the BoC forecast is correct, in terms of real GDP growth, but we get to late 2022 and inflation is at 1%? The Bank will then have a hard time justifying tightening, but they won’t be able to sustain 2% inflation without getting back to what the Bank considers the “neutral rate.”