The Mysteries of Inflation

Well, there’s nothing like a pandemic to make it clear to everyone that there’s no consensus among economists - or anyone else for that matter - about what causes inflation, or how to control it. Even people who are supposed to be controlling inflation don’t have a good fix on it. This piece will serve as an update on what’s happening with inflation - I’ll focus on the U.S. here - and the current state of my ideas on what can or should be done to control it.

We’ll start with current time series for year-over-year percentage changes in the headline pce deflator and the consumer price index. The former, of course, is the Federal Open Market Committee’s inflation measure. Given what’s laid out in the FOMC’s “Statement of Longer-Term…” that’s the measure of inflation that the FOMC targets at 2% (more or less).

But, perhaps more importantly, the pandemic has brought with it large changes in relative prices.

The pandemic is primarily a sectoral shock. Some sectors (restaurants, bars, hotels) were partially or entirely shut down (through government restrictions and private choice), while others (grocery stores, garden centers) experienced an increase in activity. And the relative prices of things consumed at home went up while the relative prices of things consumed away from home went down. On net, measured inflation went down substantially during Spring 2020, and then increased, as shown in the first chart. But, at about 1.5%, inflation (according to the Fed’s targeted measure, pce inflation) is still below target.

But where is inflation going in the future? If you sample opinions on this you’ll find a lot of dispersion, and each group seems to have its own unique concern. What are the key issues?

Measurement

Those large relative price swings shown in the second chart represent trouble for price level measures, particularly the consumer price index, which is a weighted average of prices with the weights fixed. So, for example, the CPI exaggerated the importance of prices in shut-down sectors, and therefore biased measured inflation downward in the Spring of 2020. The good news is that, in the second chart, most of the dispersion in relative prices has gone away, and part of what remains is due to secular changes in relative prices that had started before the pandemic. But, into the fall, year-over-year inflation measures will be upward-biased, given the temporarily low base in Spring 2020, and reversals in the Spring 2020 relative price movements.

Commodity Prices

Commodity prices fell at the onset of the pandemic, and have recently increased substantially.

Here, I’m including a long time series, to show that we’ve seen large commodity price swings before. Indeed, the decrease and increase in 2008-2011 were much larger than what we have seen since early 2020. It’s useful to plot commodity price inflation against pce inflation:

So, if you look at the scales on the axes in the last chart, and fit an eyeball regression line, it looks like pce inflation goes up 4 or 5 percentage points for every 100 percentage points in commodity price inflation. This is quite crude, but should relieve at least some of your concern if you think that the recent runup in commodity prices will inevitably lead to a big surge in consumer price inflation. Further, an idea driving concern about commodity prices is the “wage-price spiral,” according to which input prices increase prices of final goods and services, which induce workers to demand higher wages, increasing prices, etc. One of the useful insights Friedman left us with is that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” I think that’s true, and in this instance what it means is that a wage-price spiral can be put out of its misery by the central bank (possibly by doing absolutely nothing in terms of course-correction).

Fiscal Policy

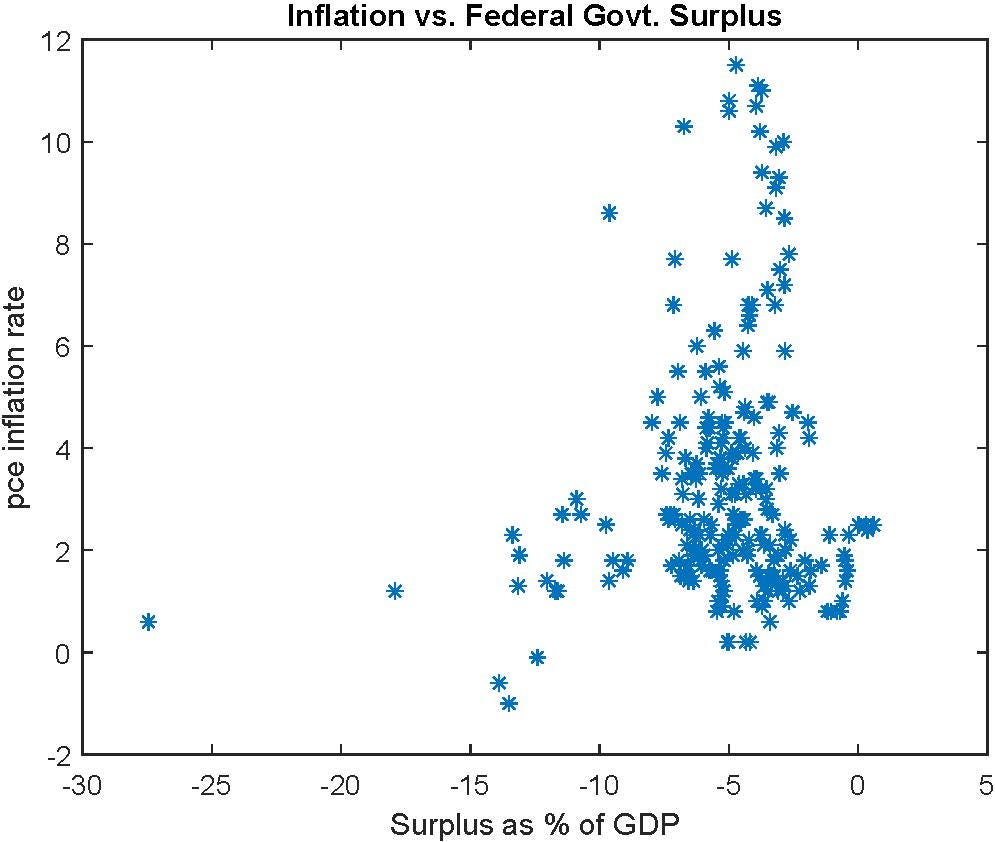

This has created some conflict, even among the otherwise-unified elder Cambridge MA types. For example, Larry Summers and Olivier Blanchard think that the ARP package will potentially cause inflation to explode. Paul Krugman doesn’t. What are people thinking about here? With Summers and Blanchard, this seems more or less an IS/LM/Phillips curve story. According to them, we may need stimulus, but not something this big. Too much stimulus produces “overheating,” apparently. That is, large deficits increase demand, but too much demand means the unemployment rate gets too low, and according to Phillips curve logic, inflation goes up. I know that there are stories about deficits during wars - the Korean War and the Viet Nam War, for example - generating inflation, but I went looking for these effects in the data and didn’t find much.

The data in the chart is for 1960-2020. I know this is crude, but I don’t see a negative correlation there. We could also look for the Phillips curve - in a similarly crude fashion - in the recent data.

What’s in the chart is unemployment rate vs. pce inflation rate, for 2009-present. Here I’m supposing that a Phillips curve person would think that inflation expectations were anchored at 2% over this period, and that the natural rate of unemployment was roughly constant. Maybe what we see in the chart is what people mean when they say the Phillips curve is flat. But, if there’s a consensus view in the Phillips curve community that the Phillips curve is flat, and you think the unemployment rate causes inflation, it seems there’s no reason to get bent out of shape about high deficits causing high inflation in the immediate future.

The other story I’ve heard about fiscal policy and inflation is a fiscal theory of the price level (FTPL) narrative. In the FTPL, the government debt is priced like any asset in basic asset pricing theory - the real value of the government debt is the present value of the expected, and appropriately discounted, payoffs on the government debt. For government debt, the relevant payoffs are future primary government surpluses. So if the government is planning a persistent increase in primary deficits, that should cause a reduction in the real value of the government debt or, given the nominal government debt, an increase in the price level. A problem with this is that what’s relevant is the entire future path for the primary primary government surplus, which of course is something we can’t observe - we’re dealing with beliefs about the future. We could deal with this by doing something analogous to how monetarists approached the inflation problem. Monetarists would typically argue that the demand for money is stable, and therefore we can predict inflation from the path for the money supply. Similarly, if the present value of anticipated future primary government surpluses is stable, this implies stable backing for the government debt, and the price level should move in proportion to the nominal government debt. Let’s try that.

The chart shows US government debt as a percentage of GDP. Under the assumptions I’ve been discussing, we should see the analogue of constant money velocity, that is a constant ratio of nominal debt to GDP, which of course is not what’s in the chart.

Another illustration of this point is in Japanese data from 1995 to the present.

From 1995 to 2019, Japanese government debt increased from under 100% of GDP to more than 230% of GDP, but the consumer price index was essentially flat. So, clearly it’s possible to have large expansions in government debt outstanding with no consequences for inflation.

There is plenty of theory and evidence to suggest that the relationship between fiscal policy and monetary policy is important. And there are plenty of examples of off-the-rails fiscal policy leading to high inflation, if not hyperinflation (see for example, Tom Sargent’s “The Ends of Four Big Inflations”). But, I think the people who gave the central bank the job of controlling inflation had the right idea. Fiscal policy can indeed create enough dysfunction that inflation runs out of control, but under the relatively “normal” conditions I envision for the immediate future, I think it’s possible for the Fed to meet its 2% inflation target on a consistent basis. Whether it will is another matter.

Inflation Control

What should give you the most confidence that inflation will stay low, after we get through the fall, is what the FOMC has told us about its policy rule. Prior to the pandemic, an idea took root in monetary policy circles that the policy tightening that had occurred between December 2015 through December 2018 had been overly aggressive. I don’t think this makes any sense. First, this was a long-delayed “normalization” of the policy rate, which had been in the planning stage since 2011. Second, relative to historical experience, this tightening cycle was more drawn-out, with a smaller increase in the policy rate. For example, it consisted of a hike of about 230 basis points in the fed funds rate over 3 years, whereas in the June 2004 to August 2006 period, the fed funds rate increased 425 basis points over a little more than two years. Finally, judged by objective measures of performance, the FOMC was successful, in that, by late 2018, the unemployment rate had fallen to 3.9%, and inflation was essentially at target, at 1.9%. So what was there to complain about?

This notion of a policy “error” helped propel a change in the FOMC’s “Statement of Longer-Run Goals…”. The change in policy amounts to some kind of quasi-inflation-averaging approach:

“…following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.”

And, here’s another important change in the longer-run goals statement:

“…the Committee’s policy decisions must be informed by assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its maximum level…”

That’s important, as it essentially specifies the second part of the dual mandate as an unattainable goal. That is, there will perpetually be shortfalls of employment from its maximum level - this isn’t some “natural” growth path around which the economy fluctuates.

So, what does that mean for actual policy decisions? The key forward guidance, from the statement for the last FOMC meeting in March reads:

“The Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and expects it will be appropriate to maintain this target range until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee's assessments of maximum employment and inflation has risen to 2 percent and is on track to moderately exceed 2 percent for some time.”

What do FOMC participants think this means for the future path of the target fed funds rate? That’s in the dot plot from the last FOMC meeting:

These are projections for each FOMC participant of the fed funds rate at the end of 2021, 2022, 2023, and in the “longer run.” So, even 32 months hence, a majority of FOMC participants is thinking that it won’t be a wise idea to be increasing the fed funds rate target from where it is now. That is, most of them think that the US economy will either be short of maximum employment, or on the low side of 2% inflation, going out 32 months. I think that majority assessment is correct. First, the FOMC can eternally argue that the US economy is short of maximum employment, which is unobservable. Second, given the projected policy, inflation less than 2% will be self-confirming.

What’s that about? I first encountered this idea when Jim Bullard was talking about it it in 2010. Jim knew about a paper by Benhabib, Schmitt-Grohe, and Uribe on “The Perils of Taylor Rules.” Basically, the idea is that, in standard macro/money models in which we know the global dynamics, a sufficiently aggressive Taylor rule (satisfying the Taylor principle) will have poor properties. That is, a Taylor-rule central banker with an inflation target, who observes inflation below target will aggressively cut the central bank’s nominal interest rate target. Unfortunately, inflation dynamics don’t work as the central banker had hoped, since they forgot to take account of Fisher effects. So, with a decline in the nominal interest rate, inflation actually falls, which leads to further rate cuts, and lower inflation. This process comes to rest at the effective lower bound, where the central banker is stuck, forever expecting a rise in inflation that never happens, and perennially undershooting the inflation target.

For me, that idea was a revelation, as it helped make sense out of some puzzling observations, in particular widespread inflation-target undershooting post-financial crisis, and 26 years (now) of average inflation at about zero in Japan. What’s that mean for the United States, going forward? The fed funds rate target has already been effectively zero for over a year now and, as I discussed above, the FOMC has locked in a view of inflation control which is likely to keep the fed funds rate target at zero going out at least into 2024. And theory and evidence tell us that persistently low nominal interest rates induce low inflation.

Conclusions? Inflation will be a little higher, maybe even above the 2% target, as measured by the pce deflator, over the next few months. But going into the fall, when I expect we’re going to be close to being back on a long-term real GDP growth trend, inflation will start to come in below the 2% target, and that’s what we’ll see for a long time, barring some dramatic change in the FOMC’s policy regime. In terms of macroeconomic performance, that will be fine, except that policymakers will at some point get agitated about below-target inflation. We like it when our central bankers just relax and do their work, in a way that’s boring to watch.