Much like in the United States (as discussed in this post), events in Canada are not unfolding as envisioned by the central bank at the beginning of the pandemic. Inflation is well above target, and the economy is behaving strangely, relative to what has happened in recoveries from previous recessions. With hindsight, some of the Bank of Canada’s forward guidance may have been ill-considered, and I think a course correction is needed.

Let’s look at the Bank’s policy statements first so we can, hopefully, understand what they think they’re doing. Then, we’ll look at the data to see if the policy makes any sense. Since early in the pandemic, the Bank has included forward guidance in its post Governing-Council-meeting policy statements. From the September 8, 2021 meeting, there are two key pieces of information, the first relating to the future path of the policy rate, and the second to the rate of asset purchases. On the policy rate,

“We remain committed to holding the policy interest rate at the effective lower bound until economic slack is absorbed so that the 2 percent inflation target is sustainably achieved.”

Here, by “effective lower bound,” the Governing Council means 0.25%. But what do they think “economic slack” is, and how are they measuring it? There’s more information in a speech given by Deputy Governor Larry Schembri on November 16. Schembri says:

“Overall, the labour market has recovered the pandemic-induced job losses, but considerable excess capacity remains. The rates of unemployment and underemployment remain elevated, especially for certain groups in the labour force.”

So according to him, slack, or “excess capacity,” can in part be measured by the unemployment rate, the “underemployment rate” (presumably some measure of discouraged workers — people not in the labor force who want to work). This statement also indicates that the Bank is interested in disaggregating data to see how different groups are being affected. Schembri’s talk goes on to talk about “maximum sustainable employment” as a concept, the output gap, and the Phillips curve as an organizing principle in inflation control. The general theme of the talk is that there is a lot of uncertainty. Maximum sustainable employment is hard to measure, and the Phillips curve may be broken, apparently. Thus there is a lot of uncertainty about what is going on, but Bank officials seem sure that, whatever slack is, it’s still there, and it’s “considerable.”

An interesting part of the Bank’s forward guidance, quoted above, is the link that’s made between disappearing slack and the Bank’s inflation target. Schembri elaborates on this in his talk:

“With an inflation target, our normal practice is to look ahead and adjust the degree of monetary stimulus to affect the level of aggregate demand and close any gap with potential output or aggregate supply. With inflation expectations well anchored at 2 percent, inflation should sustainably come back to target when economic slack is absorbed and the economy returns to maximum employment.”

So, that’s an odd way to put it. If the Governing Council is guided by macroeconomic theory, best guess is that’s New Keynesian (NK) macro. But in a baseline NK model, the policy rule Schembri specifies would not “anchor” inflation expectations at 2%. For example, consider two policies: (i) low nominal interest rate target forever; (ii) high nominal interest rate target forever. In the absence of any further aggregate shocks, in an NK model the output gap (which is well defined within that framework) will disappear, but the inflation rate will be higher under the second policy.

To have it make sense, within the NK paradigm, we need to add to Schembri’s policy rule some notion of a neutral policy rate, along with a description of how the Bank responds to inflation. In its October Monetary Policy Report, it’s stated:

“The neutral nominal policy interest rate is defined as the real rate consistent with output remaining sustainably at its potential and with inflation at target, on an ongoing basis, plus 2 percent for inflation. It is a medium- to long-term equilibrium concept. For Canada, the economic projection is based on an assumption that the neutral rate is at the midpoint of the estimated range of 1.75 to 2.75 percent. This range was last reassessed in the April 2021 Report.”

So, as far as we know, the Bank still thinks that, roughly, a neutral rate of 2.25% is about right. The press release from the October 27 meeting sees slack disappearing sometime during the period April-September 2022, with inflation returning to 2% by the end of 2022 in the Bank’s projections. But the Bank’s forward guidance says that increases in the policy rate don’t happen until the slack goes away. So it’s hard to see how the forward guidance, the Bank’s own forecast, and the framework described in the Bank’s literature are all consistent, as the Bank seems to be planning for a policy rate far below 2.25% at the end of 2022.

A key development in Bank policy has been the steady reduction in the rate of purchases of long-maturity Government of Canada bonds. At the October meeting, the Bank announced that it was entering a “reinvestment” phase, meaning that, as the Bank’s bonds mature, they will be replaced in the Bank’s asset portfolio. Therefore, for the time being, the nominal value of bonds held by the bank will be held constant. In the press conference following the meeting, Governor Tiff Macklem appeared to signal that reinvestment would end at some point, but the Bank has not been clear about what is to follow. In particular, it would be useful to know whether the bank intends to have a large balance sheet (as in the United States) over the long term, or if it intends to revert to the system in place in Canada prior to the pandemic.

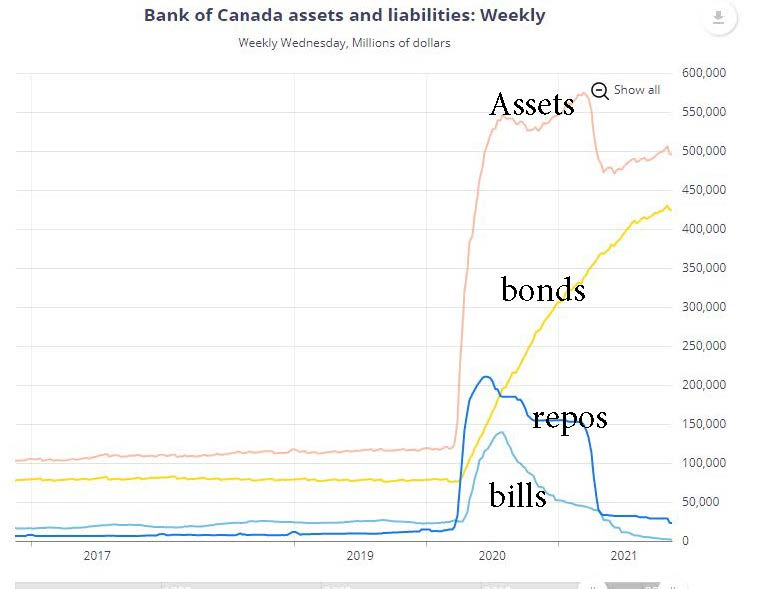

Here are the key entries on the asset side of the Bank’s balance sheet:

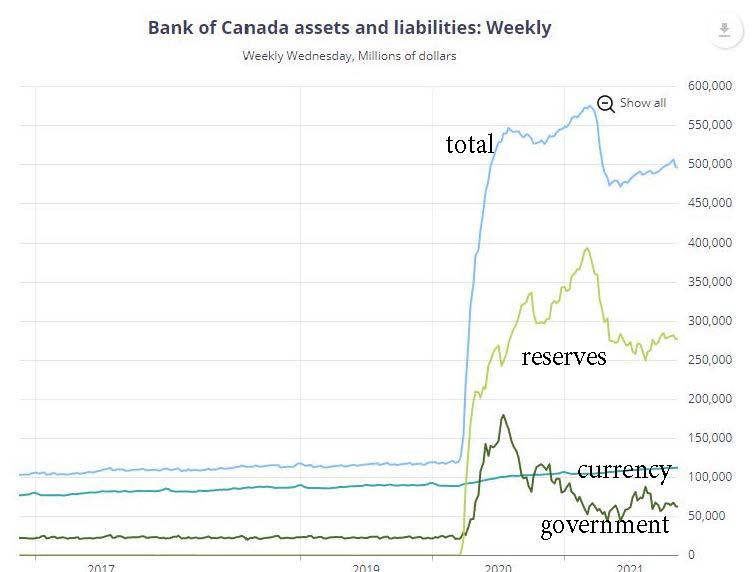

And here are the liabilities:

Part of what’s interesting here is that the Bank’s bond purchases have been offset by reductions in its holdings of Treasury bills and its lending through the repo market. So, on net, total assets are lower than earlier in the year, but average maturity has increased. On the liabilities side, total settlement balances (reserves) are down from early 2021, currency outstanding is up, and federal government balances held with the Bank are about the same.

So, if one thinks that quantitative easing (QE) works through the size of the balance sheet, or the quantity of reserve balances held by the banks, then the Bank has been backing off QE for some time, even before the Bank formerly announced the end of net positive asset purchases at the October meeting. I tend to think that QE has little or no positive economic effects, and that its only role in this context is to delay increases in the policy rate. That is, the standard central bank playbook now seems to be that QE programs are wound down before policy rate increases can happen. So, in contrast to the Fed, which will not be finished with asset purchases until mid-2022, the Bank has more policy options in the short term.

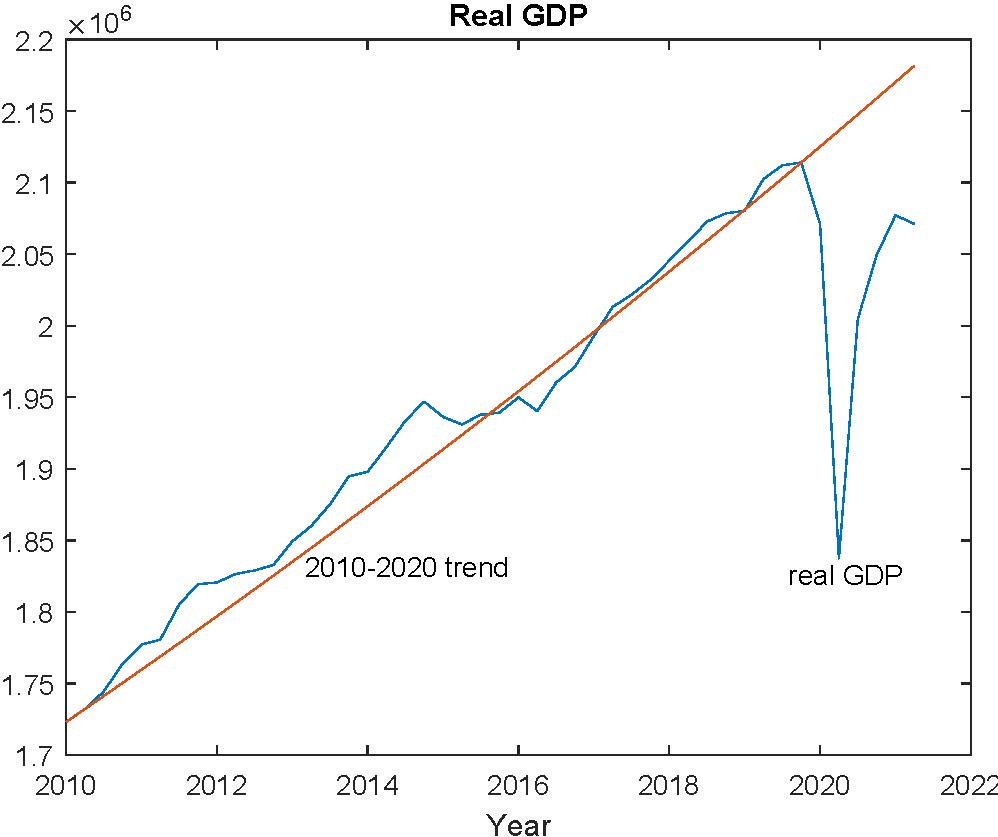

So, let’s look at the macro data. Real GDP in Canada looks like this:

The recovery in real GDP has been more swift than in a typical recession, but real GDP is currently 5.1% below the 2010-2020 trend. The labour market data looks better, though.

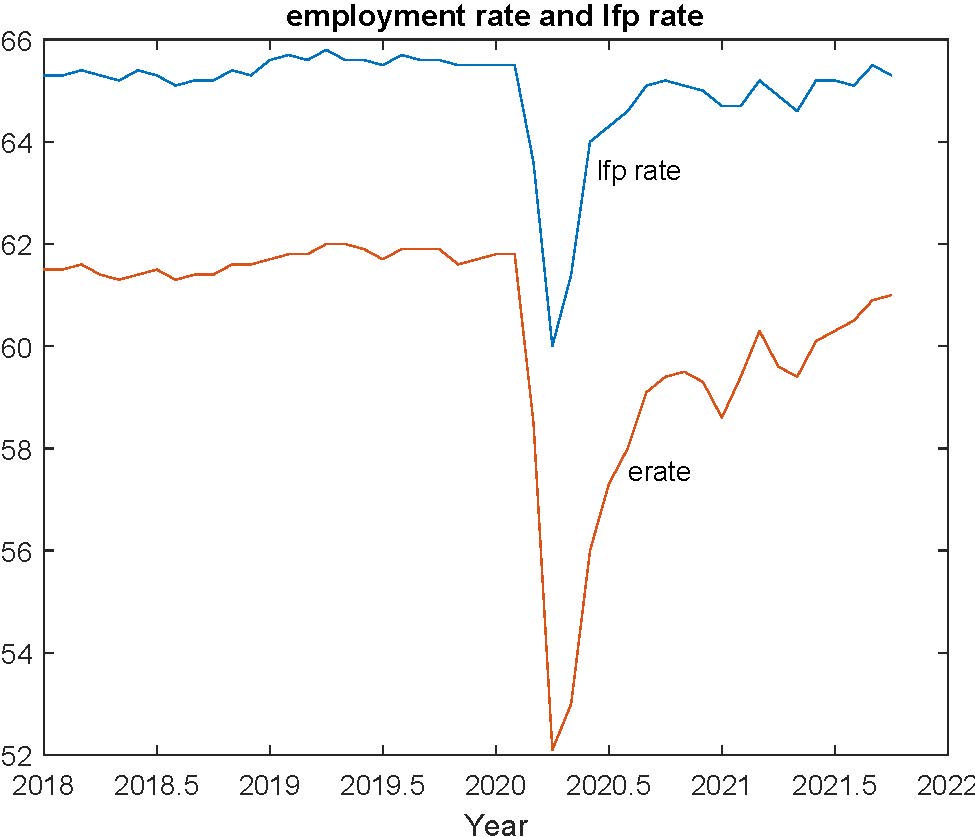

The labour force participation rate is about where it was prior to the pandemic, and the employment rate is almost there.

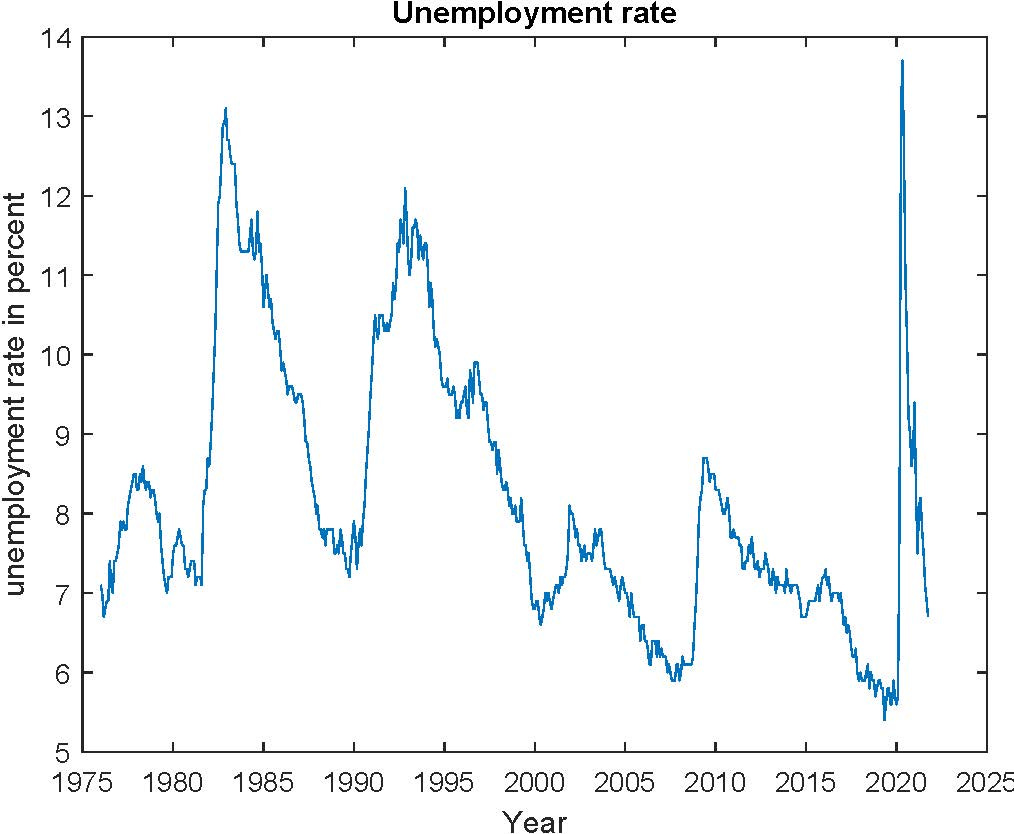

The unemployment rate, currently at 6.7%, is higher than it was in Janaury 2020 (when it was 5.6%), but the same as in March 2017 or October 2005, which we wouldn’t characterize as bad times. Also, as in the U.S., the vacancy rate is high. The vacancy rate in Canada in 2021Q2 was 4.6%, higher than the 3.0% recorded in 2019Q4, indeed a higher vacancy rate than in the entire sample, which goes back to 2015.

So, I think we could characterize the Canadian labour market as tight, in the aggregate (we’ll discuss sectoral issues later). In this sense, there is no slack. This looks like an economy with low productivity — because of pandemic restrictions on activity, fear of contagion, and disruption in production, transportation, and retail activity — and it’s basically producing all it can.

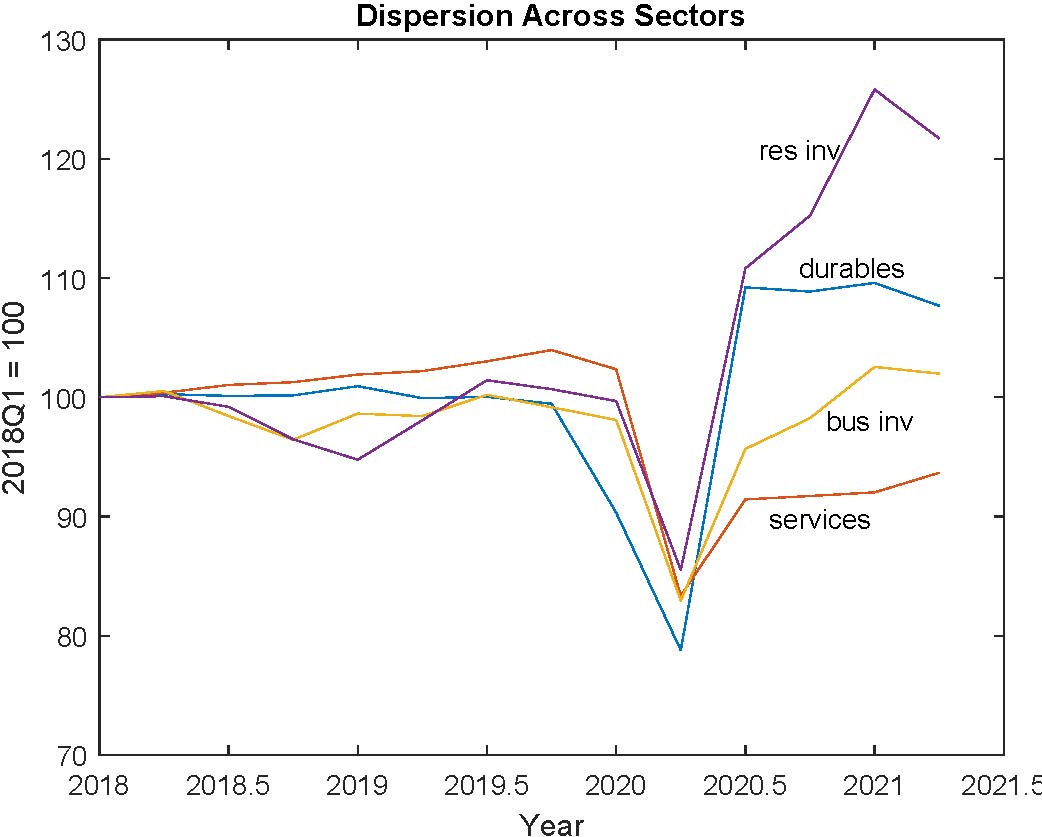

An interesting feature of the pandemic is that it’s a sectoral shock, which I’ve illustrated here by looking at some components of GDP.

In the figure I’ve normalized each time series to 100 in 2018Q1. So, residential investment and consumption of durables are much higher than pre-pandemic, while total business investment is lower, and consumption of services is much lower.

In the press release following the October Governing Council meeting, it’s stated:

“… the economy continues to require considerable monetary policy support.”

But, according to how the Bank thinks about the problem, that support is being provided to sectors that are most responsive to interest rates, at the short and long ends. Including residential construction, and consumer durables, which apparently are booming, i.e. not in a state of “ongoing excess capacity,” as the October press release states as the reason for continuing accommodative policy.

Finally, of key importance of course, is the recent behavior of inflation. Here, it’s key to emphasize that the Bank’s current agreement with the federal government states:

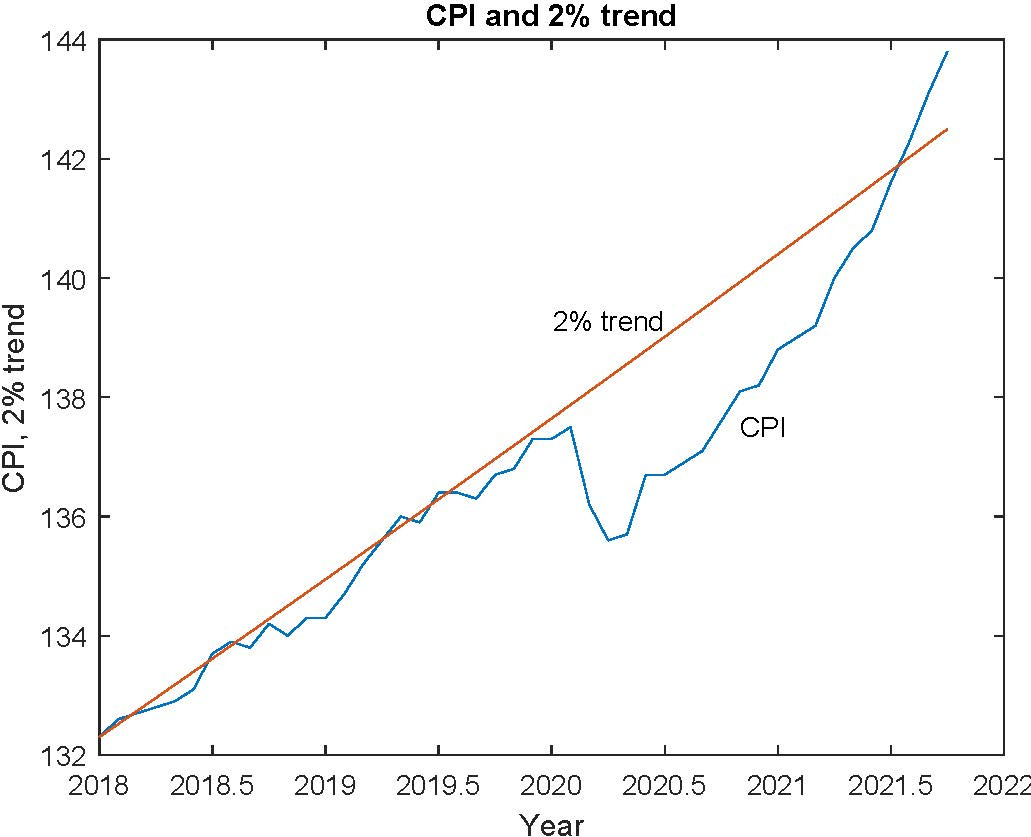

“…the Bank will continue to conduct monetary policy aimed at keeping inflation, as measured by the total consumer price index (CPI), at 2 per cent, with a control range of 1 to 3 per cent around this target.”

Inflation is currently at 4.7% (October), year-over-year, which of course is well outside the 1% to 3% range. Even if the Bank were pursuing some type of makeup strategy, it would have made up more than the undershoot in 2020, with average inflation above 2%, even if we go back to 2018.

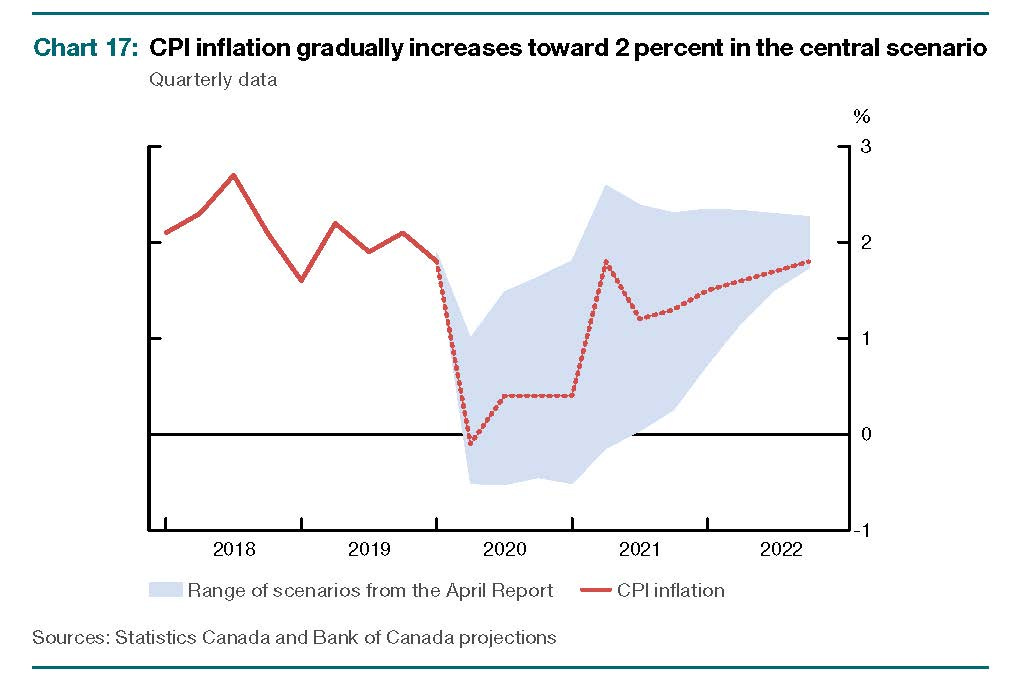

So, this inflation behaviour was not what was envisioned when the Governing Council wrote down its forward guidance. For example, here’s the Bank’s inflation projection from the July 2020 Monetary Policy Report:

So, note in particular that actual inflation behavior in 2021 is outside even the shaded area, which appears to be a confidence interval. So, the Bank’s mandate is inflation control, as specified in its agreement with the federal government. Inflation is well outside the range specified in that agreement. But the only change in the Bank’s policy has been to move up by a few months the vaguely specified date at which it might consider increases in its policy rate. Note in particular that the reductions in asset purchases were hardwired — these reductions were set in motion long before high inflation was on the map. That is, apparently the Bank decided, almost a year ago, that purchases would fall in steps of $1 billion per week, at every other Governing Council meeting.

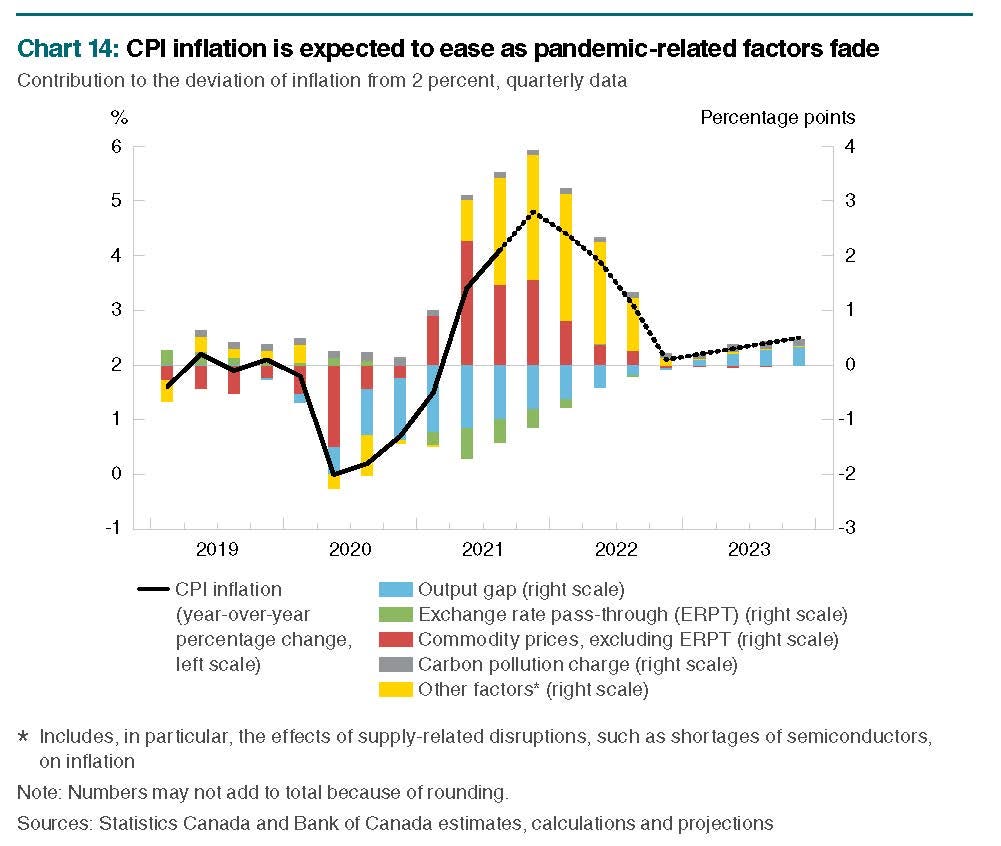

But, the Bank’s story (as with the Fed) is that the increase in the inflation rate is temporary. That’s what’s in their forecast (from the October Monetary Policy Report):

Note here that they have the inflation rate peaking in 2021Q4, then declining to close to 2% by 2020Q4. So, I don’t have any good reasons to argue with that, but I don’t think that forecast (or anyone else’s) is worth much right now.

As I’ve argued, there do not exist good reasons for continuing with low interest rates. Though the economy is still adjusting to the sectoral disruption caused by the pandemic, the labour market is tight, the aggregate economy is operating at capacity as far as we know and, of course, inflation is well above target. In the short term there is little harm in increasing the overnight interest rate target in 25-basis-point steps — this won’t make the economy fall off a cliff. Sooner or later, the policy rate needs to go up to a level that is conducive to supporting 2% inflation over the long run, and given current conditions, it’s appropriate to start moving ASAP.

Robert C. Merton, in an article written for Pensions & Investments (pionline.com, "Monetary policy: It's all relative", April 16, 2015) observed "One of the goals behind quantitative easing in the U.S., Europe and even Japan has been to pursue the 'wealth effect'--pumping up the value of assets to make individuals richer, thus getting them to spend more and, thereby, prevent deflation. Furthermore, the belief that lower long-term interest rates leads to more investment has led the Federal Reserve, and now the European Central Bank, to depress long-term interest rates." He and his co-author, Arun Muralidhar, argue that "...while QE has increased absolute wealth, it has simultaneously lowered relative wealth for a large class of investors. ... Lower wealth means investors need to save more to improve their funded status, esp. where regulations are strict... and it results in less consumption and investment, and may not remove the deflationary overhang." Five years on, it is evident that the "deflationary overhang" was a remote risk. The original intent of QE justified its initial use, but its continued use is of doubtful effect. The composition of the Bank's asset portfolio indicating the surge in bonds and the decline in bill and repo holdings suggests that the Bank is focused on lowering, or keeping low, longer term interest rates (5 year - 10 year term debt), and this may be why residential investment has climbed so high while business investment as remained stationary, relative to historical levels. Residential investment responds to the mortgage rate, and repressed interest rates (yields) at the 5-year maturity bonds achieved through a change in the composition of assets acquired via QE may be an explanatory factor in the rapid increase in residential investment. If the Bank pulls back further in QE acquisitions of government bonds, then the practical effect will be an upward reset of mortgages rates and a decline in residential investment. Since residential investment does tend to crowd out other forms of investment, tapering QE sooner rather than later may improve investment in productive capacity somewhat, ceteris paribus, even as it reduces employment and lowers consumption spending. Steepen the yield curve to address Merton's and Muralidhar's concern over financial oppression, while leaving the over-night rate at its current low level to avoid raising the inflation rate higher (Fisher effect), might be the correct policy response.