Jay Powell's April 28 Press Conference

There was nothing new in the statement from this week’s FOMC meeting, but I watched Powell’s press conference from yesterday, and I think there are some interesting things to report. Mostly this relates to the Fed’s forward guidance, Fed communications, and the new quasi-average-inflation-targeting approach.

In his press conference, Powell was doing essentially everything an intelligent lawyer could do to articulate monetary policy to the public. He sometimes reads directly from prepared material, he’s clearly well-briefed, he’s worked hard to understand what’s going on, and he doesn’t deviate from the script. People are not directing animosity (any more than is usual) toward the Fed, and part of the reason for that is that Powell does a good job of projecting genuine empathy. That said, I think there are flaws in how the FOMC thinks about policy, and Powell’s lack of economics training - and a general move toward non-economists on the committee - doesn’t help in that regard.

To get up to speed, the forward guidance in the FOMC statement refers to the future path for the policy rate, and asset purchases. First, the policy rate:

“[The FOMC] expects it will be appropriate to maintain this target range [0-0.25% for the fed funds rate] until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee's assessments of maximum employment and inflation has risen to 2 percent and is on track to moderately exceed 2 percent for some time.”

Next, asset purchases:

“…the Federal Reserve will continue to increase its holdings of Treasury securities by at least $80 billion per month and of agency mortgage‑backed securities by at least $40 billion per month until substantial further progress has been made toward the Committee's maximum employment and price stability goals.”

Some of the questions Powell got in the press conference were aimed at getting him to be more specific about what those words mean. And the words in the FOMC statement aren’t written off the cuff - they’re carefully chosen, and discussed extensively by FOMC members. So, we should expect the meaning to be clear, right? But, since the FOMC only “expects” to move the policy rate in a way consistent with its current guidance, how is the guidance supposed to help us? What’s a level for labor market conditions consistent with maximum employment, and what conditions are we talking about? What’s “moderately” mean, in specific quantitative terms? How long is “some time?” How could I measure “substantial,” and what would it mean to “moderately exceed” 2% inflation?

Pressed on some of these things, Powell repeated the words in the statement, or referred back to the “Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy.” He insisted that the forward guidance is “outcome-based.” To me, that would mean that the forward guidance specifies future actions contingent on observable outcomes - that is, outcomes that we all can observe. Clearly, the forward guidance does nothing of the kind. The outcomes are in the minds of FOMC members, and the actions triggered by the outcomes are also something of a mystery. So, a good question would be why the FOMC bothered to write down any forward guidance at all, if what they wrote down has so little content.

But did Powell say anything in the press conference that might help us understand how the FOMC is likely to behave in the future? A couple of questions came up to do with what might happen if high inflation - more than moderately-exceeding 2% for some time, I guess - were to rear its ugly head. In particular, what if the economy is not at maximum employment, but inflation exceeds 2% by a large amount. Powell insisted that “we understand our job,” and that the Fed would “use its tools” to control excessive inflation, referring to the “Statement of Longer-Run Goals…” which deals with what the FOMC should do if the two parts of the dual mandate are in conflict. Problem is the “Statement of Longer-Run Goals…” is in conflict with the current FOMC statement, which says the policy rate stays where it is as long as we’re below “maximum employment.”

An overriding theme in the press conference is that, according to Powell, we have a long way to go, both in terms of seeing “substantial further progress,” (which would trigger tapering of asset purchases) or “maximum employment.” Indeed, the dot plots from the last FOMC projections that were issued suggest that FOMC members think they won’t be increasing the policy rate until early 2024. But this is no ordinary recession. Some sectors are already doing quite well - housing in particular:

Currently, housing starts are at their highest level since the financial crisis. Presumably the housing sector is a primary target of the Fed’s QE program, as the FOMC sees it. So why does that sector need continuing stimulus? You might think the Fed should be warming us up for a phasing-out in their asset purchase program.

As well, job openings are plentiful:

In this chart, I’ve plotted the ratio of job openings to the number of unemployed - a standard measure of labor market tightness. So tightness is well down from early 2020, but at about the same level as in 2016 or just prior to the financial crisis. So that’s not a depressed job market.

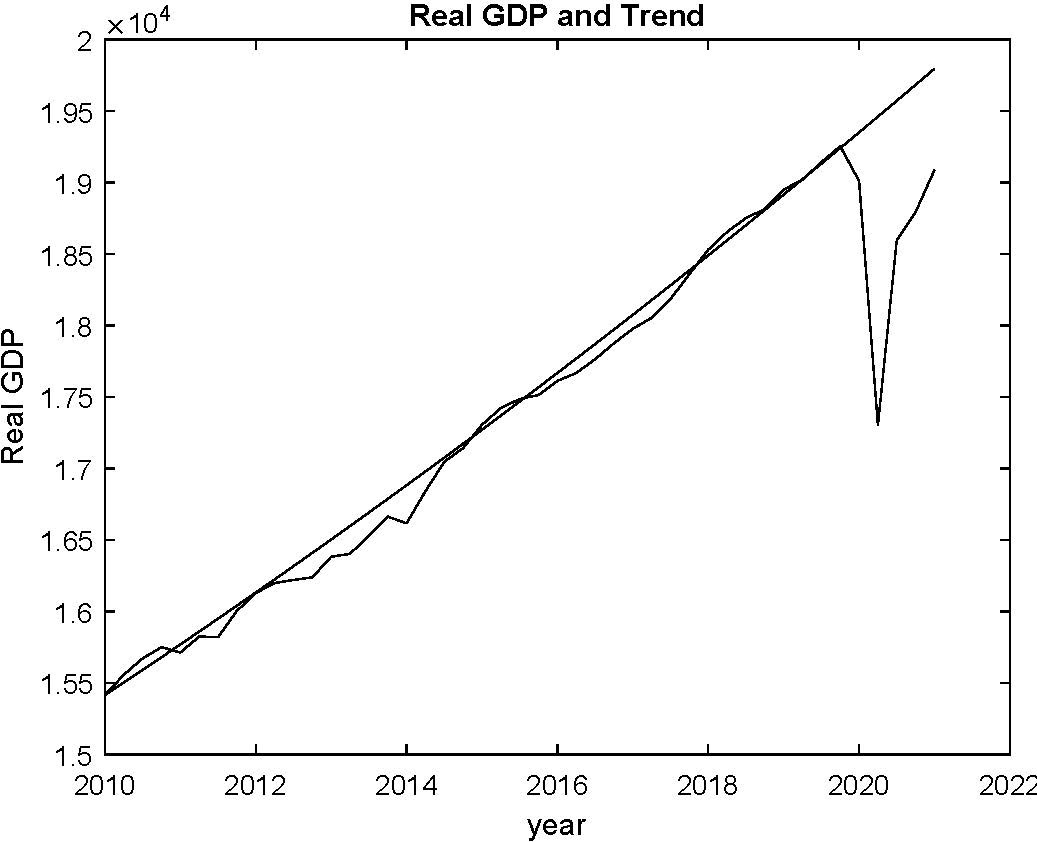

Though Powell didn’t want to be nailed down about how he might measure “maximum employment,” I think he’s focused on getting back to some sort of long-run trend. For example:

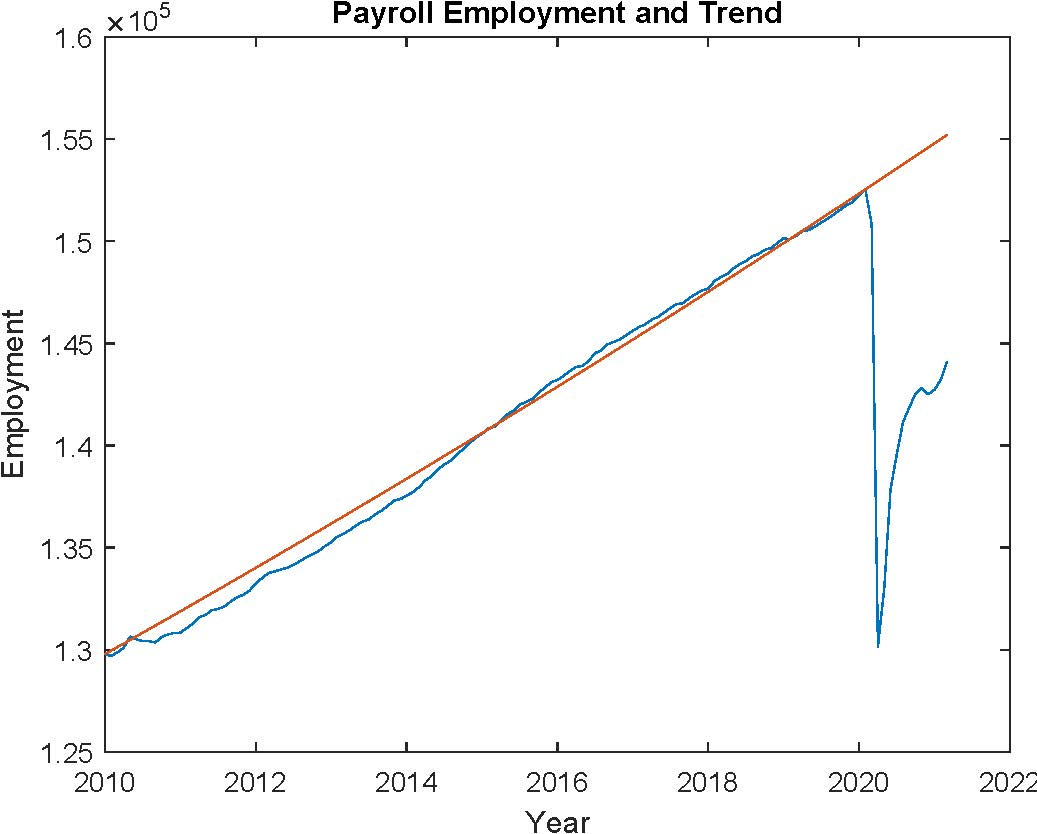

That chart isn’t great, but I think you can tell which is actual real GDP, and which is the 2.3% growth path (average rate of growth, 2010Q1 to 2021Q1). So according to the chart, we don’t have that far to go. Real GDP is currently 3.6% below the trend. The shortfall relative to trend is larger, though, if we look at employment:

That is, employment is currently 7.1% lower than the 1.6% growth trend. That difference (relative to the real GDP chart) seems to be due to the fact that the large drops in employment occurred in low-productivity sectors (essentially by definition).

So, this looks to me like an economy that’s being held back primarily by COVID. That seems obvious of course, but the point is (again) that this is no ordinary recession. As Powell pointed out, neither households nor banks are financially stressed, as they normally would be when we’re pulling out of a recession. So, once people are vaccinated, the summer and fall start to look pretty good. We could have all the bugs worked out by early next year. The caveats have to do with what is going on in the rest of the world where, in some cases, vaccination on a large scale is just starting, and with the unpredictable nature of coronaviruses.

With respect to inflation control, my concerns were stated, for the most part, in my previous post. The Fed’s new quasi-average-inflation-targeting approach is based on the idea that, if a central bank keeps its policy rate low for a sufficiently long time, then inflation will surely go up. Unfortunately, that doesn’t happen, in theory or practice. It’s belief in that idea that has caused any number of central banks to undershoot their inflation targets. So, unless ideas change on the FOMC, the most likely future is one where inflation and interest rates stay low. That’s OK, but it won’t make Fed officials look like they know what they’re doing.