The Fed's Policy Implementation Framework Does Not Work As Advertised. How Come? Part II

The Floor That's Not a Floor

[Make sure you read Part I first. I had to split this in two as it exceeded Substack’s email limit.]

I’ll repeat Figure 9 from Part I for easy reference:

Figure 9:

The last thing to note about Figure 9 is that, in early 2018, the interest rate differentials you see before then disappear, coincident with the phasing out of Fed asset purchases. Recall that this is also the time that ON-RRP activity drops dramatically, but not to zero. So, for the most part, when the Fed is no longer purchasing assets, the ON-RRP facility is not needed to the same extent to prop up the overnight repo rate from below.

But that’s not the end of the story:

Figure 10:

Figure 10 shows the repo rate (blue, that’s SOFR), IOER (green), fed funds rate (purple), and 4-week T-bill rate (red), from January 2019 until the pandemic hits. Three of those interest rates track each other fairly closely over this period, but what stands out is the behavior of the repo rate. Remember the end-of-month downward spikes in the fed funds rate in Figure 9? Well, in Figure 10, those are end-of-month upward spikes in the repo rate, which start happening in early 2019, as reserve balances are falling.

Then, on September 17, 2019 (perhaps surprisingly, not a month end), a large shock to the overnight market (more on that in what follows) resulted in the spike you see in interest rates in Figure 10, with the largest effect on the repo rate. Again, that’s not supposed to happen in a floor system, theoretically. Relative to what was going on in 2016-2018, the stress is on the other side of the repo market, appearing as upward pressure on SOFR rather than the downward pressure that the NY Fed was accustomed to mitigating with the ON-RRP facility. So, perhaps unsurprisingly, the Fed began intervening by lending in the repo market, which we saw in Figure 5 in Part I. The Fed intervened by lending on the repo market at IOER which, as you can see in Figure 10, served to essentially peg the fed funds rate, SOFR, and the 4-week T-bill rate to IOER. But of course what was happening was that the Fed was varying the quantity of repos on its balance sheet day-to-day to peg SOFR, just as it would pre-financial crisis. You may be getting the idea that this isn’t really a floor system.

Regarding the September 2019 event, this note written by Board of Governors economists is very interesting. Posted in February 2020, it makes the case that a number of special factors contributed to the spike in overnight rates in September 2019, and discusses the Fed’s response. Essentially, the special factors cited in the note read like the usual laundry list of shocks - unanticipated and anticipated - that the Fed normally has to deal with, through daily intervention, when a corridor system is in operation. Two things are surprising here. The first is that the note gives you the impression that the factors that led the Fed to intervene in September 2019 were temporary, but of course the repo intervention continued at similar levels into the pandemic, as you can see in Figure 5 in part I. The second surprise is that there’s no mention of this episode being abnormal in terms of how anyone - in or outside the Fed - thought floor systems should work. The Fed was saying: “no problem, everything is fine here - and pay no attention to the man behind the curtain.”

Finally, we’ll look at interest rates in the recent past:

Figure 11:

This is data for the same four interest rates as in Figure 10, but for the pandemic period. In Figure 11, there’s first a period of turmoil, and then things settle down from fall 2020 until early in 2021. That period of calm, when SOFR, the fed funds rate, and the 4-week T-bill rate are pegged at one or two basis points (mostly) below IOER, is a period when there was no intervention by the Fed on either side of the repo market, as we saw in Figure 5 - essentially the only time that occurs in the whole period from December 2015 (liftoff) to now. But, in early 2021, when the volume started to increase on the Fed’s ON-RRP facility, there was downward pressure on overnight rates, with SOFR and the T-bill rate effectively pegged by the ON-RRP rate.

So, we’re now back to the regime of 2016-2018, when the Fed was making large asset purchases, the stock of reserves was increasing, and ON-RRP intervention was pegging the overnight rate. Except now it’s more extreme, as ON-RRP volume is getting very high.

Here’s another interesting tidbit. In Jay Powell’s June 16, 2021 press conference, Michael Derby asked a question about the high takeup on the ON-RRP facility. Powell answered:

“So on the facility, we think it's doing its job. We think the reverse repo facility is doing what it's supposed to do, which is to provide a floor under money market rates and keep the federal funds rate well within its range. So we're not concerned with it. You have an unusual situation where the Treasury general account is shrinking and bill supply is shrinking. And so there's downward pressure. We're buying assets, there's downward pressure on short-term rates, and that facility is doing what we think it's supposed to do.”

So, three things. First, the facility is doing what it’s supposed to do alright, but the Fed claims the floor is simpler than operating a corridor, while effectively conducting intervention as if operating a corridor. Second, the business about keeping the fed funds rate in its range is baloney. There are two interest rates that matter in this system, the way the Fed operates it. Those rates are the ON-RRP rate and the rate at which the Fed is willing to auction repos. Those rates bound SOFR from above and below. There can be unusual circumstances where the Fed is both borrowing through ON-RRP and lending by way of repos. But typically whichever facility is operative - the ON-RRP facility or repo auctions - is going to determine what SOFR is pegged at, the ON-RRP rate, or IOER, which is the rate at which repos are auctioned. The fed funds rate is not bounded by the ON-RRP rate on the low side, and IOER on the high side, except to the extent that repos and fed funds borrowing and lending are close substitutes. Third, in his comments, Powell is following a pattern that tends to show up in Fed discussions of anomalies in the operation of its floor system. That is, blame the Treasury. That’s inappropriate I think, as the Fed is quite capable of setting things up so that Treasury actions don’t impinge on monetary policy.

What’s Going On?

The frictionless version of my alternative model in Figure 4 of part I clearly falls short of explaining what is going on, as it tells us that, given an outstanding stock of reserves, IOER should peg the overnight rate. I’ll modify Figure 4, and then discuss what potential frictions are limiting arbitrage in the overnight market.

Given our examination of the data, it seems the Fed’s floor system works in two modes. In the first mode, in the absence of Fed intervention in the repo market, markets clear with IOER > overnight rate.

In periods when the Fed’s ON-RRP facility was operational (seemingly with a relatively high volume), the situation without ON-RRP intervention would look like Figure 12, if there were no ON-RRP intervention. Reserves are willingly held by banks with IOER = R*, but the overnight market clears with the overnight rate R** < R*. So, you would think that that unexploited profit opportunities exist here. For example why don’t banks without reserve accounts that are lending at the overnight rate R** obtain a better deal by lending to banks that can hold reserves at the rate R*? Typically, the answer would be that there are costs for a regulated bank, in addition to the interest payment they might pay to a non-bank lender, to acquiring funds and holding reserves. For example, deposit insurance premia apply to all assets, not just risky assets, and capital requirements, for example the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR), also apply to all assets. The flip side of this is that R* > R** reflects a desire by banks to unload their reserves - the Fed has to pay banks a premium above overnight rates (which as we’ve seen are pegging T-bill rates) to get banks to hold the reserves.

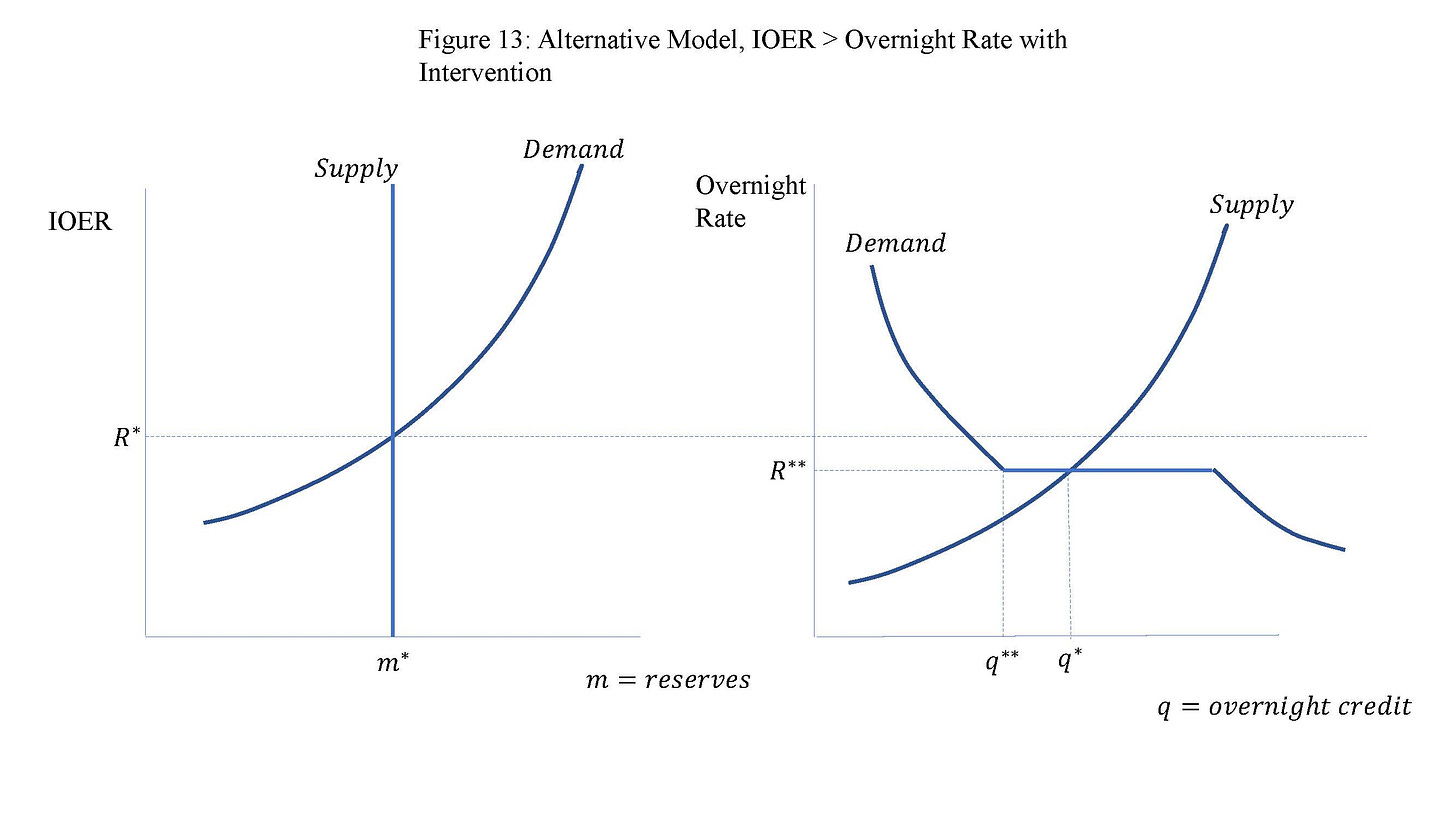

But, in a situation like Figure 12, the Fed may not like the result, as it wants to peg the overnight rate higher than R**. What to do? That’s where the ON-RRP facility comes in:

So note, comparing Figure 13 and Figure 3 from Part I, that the mechanics of how the Fed’s intervention works to peg the overnight rate are the same as in a corridor system, as effectively this is a corridor system, in the sense that IOER is not determining the overnight rate - that’s determined by how the Fed intervenes in the repo market. But what’s the difference between Figure 13 and Figure 3? Of course, its that the Fed has a large stock of interest-bearing reserve liabilities that are confined to the banking system. The reserves want to get out of the banking system, as reflected by R** > R*, and the ON-RRP facility gives the reserves an escape valve.

Currently, it looks like what happens, roughly, is that $1 of extra asset purchases goes into ON-RRP liabilities, not reserves. The current situation looks like a case where the banking system has a glut of reserves, and marginal asset purchases by the Fed are funded with reverse repos. But why wouldn’t the Fed just set the ON-RRP rate equal to the interest rate on reserves, following the logic of how they intervene on the other side of the market, where the Fed lends in the repo market at IOER? Well what might happen in Figure 13 if the Fed pegs the overnight rate at R** = R* is that all the reserves turn into reverse repos. You would think the Fed would like this, as they could talk about policy in terms of a single interest rate target instead of a range, but I’m guessing the issue is that they’re wedded to the idea that stuffing reserves into the banking system actually does something useful. They learned about the money multiplier in money and banking class? Who knows.

Next, let’s think about what was going on during the period January 2019 to early 2020 when overnight rates were being pushed above IOER.

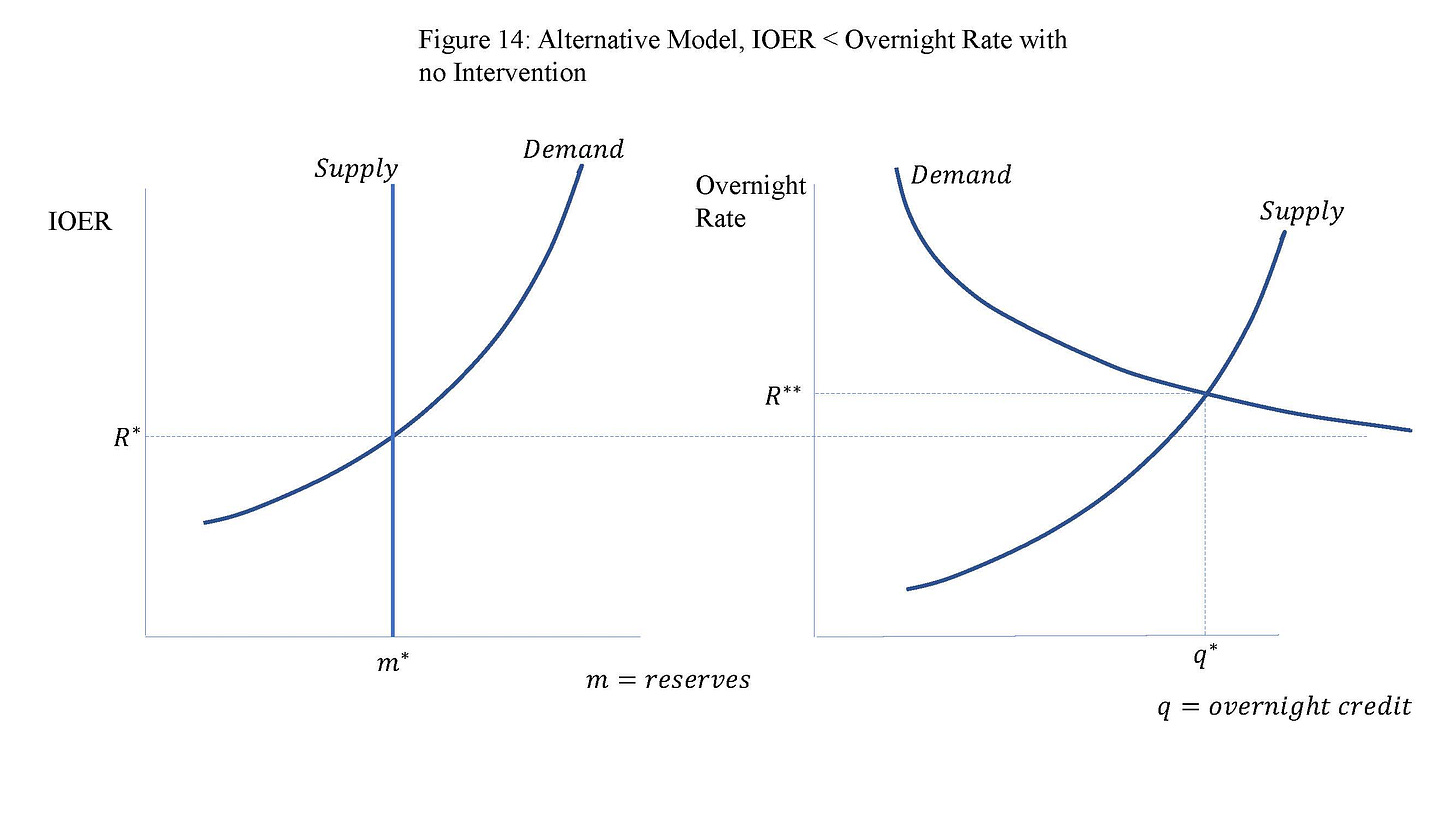

In Figure 14, with the absence of Fed intervention in the repo market, the overnight credit market clears with the overnight rate R** above IOER, which is set at R*. We’ve covered what could be going on in terms of bank regulation and limits to arbitrage when R** < R*, but what’s happening here? Why are banks willing to accept a low return on holding reserves when it seems it would be more profitable to lend in the overnight market?

In order to substitute from reserves to overnight repos in the short run, a bank would have to sell some liquid assets. Principally, those liquid assets are reserves and Treasuries. A bank can get rid of reserves, but only by selling them to another financial institution with a reserve account. But, basically, the banking system can only shuffle the reserves around - it can’t jettison the reserves, except through the the ON-RRP facility, and that’s inoperative in this case. What about Treasuries? First, if all banks had binding liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) constraints, then in some sense the Treasuries are locked up too. LCR requires that banks hold a specified ratio of liquid assets to total net cash flows. The constraint can be satisfied with other than high-quality liquid assets (HQLA - reserves and Treasuries), but the weights on other assets in calculating the ratio are lower. Second, if the overnight rate is high, so is the T-bill rate, so banks get a high return on T-bills and may choose not to sell T-bills to lend in the repo market.

So, there seem to be good reasons to think there are significant arbitrage frictions present that could cause R** > R*, and that’s certainly what we observed in September 2019. What’s the solution? The Fed can intervene by lending in the repo market.

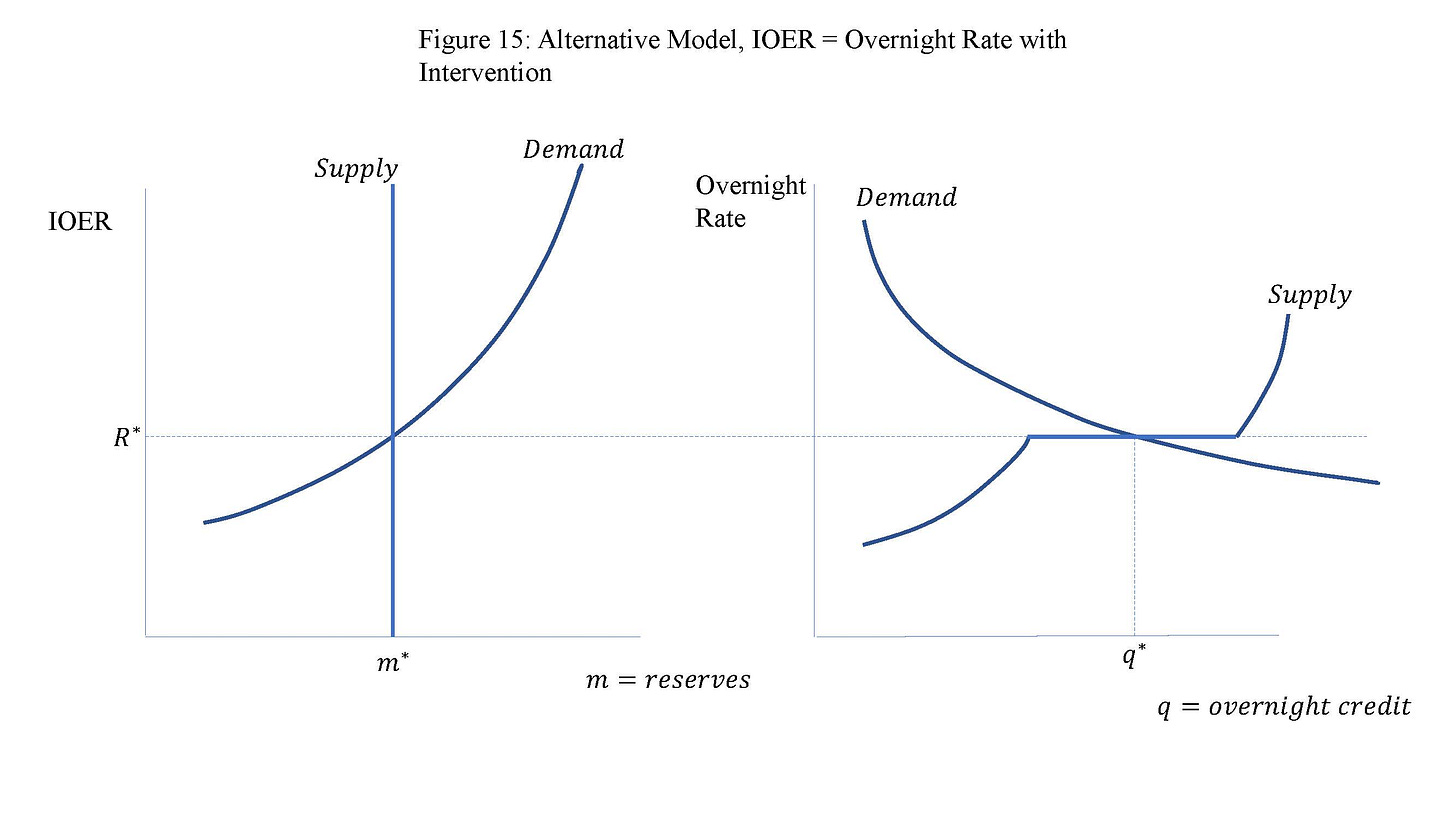

Probably you can predict what’s coming next. In Figure 15, the Fed intervenes by acquiring overnight repos, and pegs the overnight rate at R*, which is also IOER. First, the overnight market intervention is exactly the same as in Figure 2, which models what the Fed was up to in overnight markets pre-financial crisis. Second, what’s perhaps most important is that IOER is not pegging anything. For example, in Figure 15, the Fed could peg the overnight rate below IOER if it wanted to. This is a system where IOER is not a floor, and it’s not a ceiling either. Again, this is just Fed intervention working in the usual way, but with a big stock of reserves outstanding.

A proposal that came from within the Fed well before September 2019, was that the Fed set up a “standing repo facility.” Such a facility is not unusual, for example the Bank of Canada has an overnight standing repo facility, which appears intended to supplement lending through the equivalent of the U.S. discount window, at the equivalent of the discount rate. But the proposed Fed standing repo facility appears to be directed at making the floor system work better, not at making the discount window work better. It seems that people in the Fed have convinced themselves that the problem that created the events of September 2019 is that banks like reserves too much, that Treasury securities are not liquid enough, and thus the demand for reserves is higher than it should be. So, according to this argument, there’s a problem that can be mitigated through a standing repo facility that allows banks to conveniently unload Treasuries, along with other assets, depending on what the facility accepts as collateral.

So, the standing repo facility seems harmless enough, but the problem people say it will correct is, I think, not a problem. The actual problem is that the reserves are illiquid. Sure, reserves are daylight settlement balances among financial institutions with reserve accounts, but they are not acceptable means of payment for any economic entity without a reserve account. Reserves are locked up in the banking system and, in the situation depicted in Figure 14, the reserves cannot escape. For the banking system as a whole, reserves are illiquid. So, the problem is the floor system, not the “illiquidity” of Treasury securities.

What’s This Mean For QE?

So, I think we have determined that any claim that the Fed’s floor system eases fulfillment of the FOMC’s policy rate directive is a bogus claim. Most of the time, the Fed is basically intervening in the same way it did before the advent of the floor system. The only differences are that: (i) sometimes it intervenes through reverse repos rather than repos; (ii) the NY Fed is pegging SOFR, not the fed funds rate.

Where does that leave us? The “floor” system is about QE, that is turning Treasury securities and MBS issued by GSEs (government sponsored enterprises) into reserves. That is, the Fed has decided that it wants to get into the business of debt management. Purchases of long-maturity Treasuries by the Fed reduces the quantity of those securities that are publicly held, and increases the stock of reserves held in the banking system. Purchases of MBS do nothing to the stock of Treasuries, but reduce the stock of MBS held by the public and increase reserves.

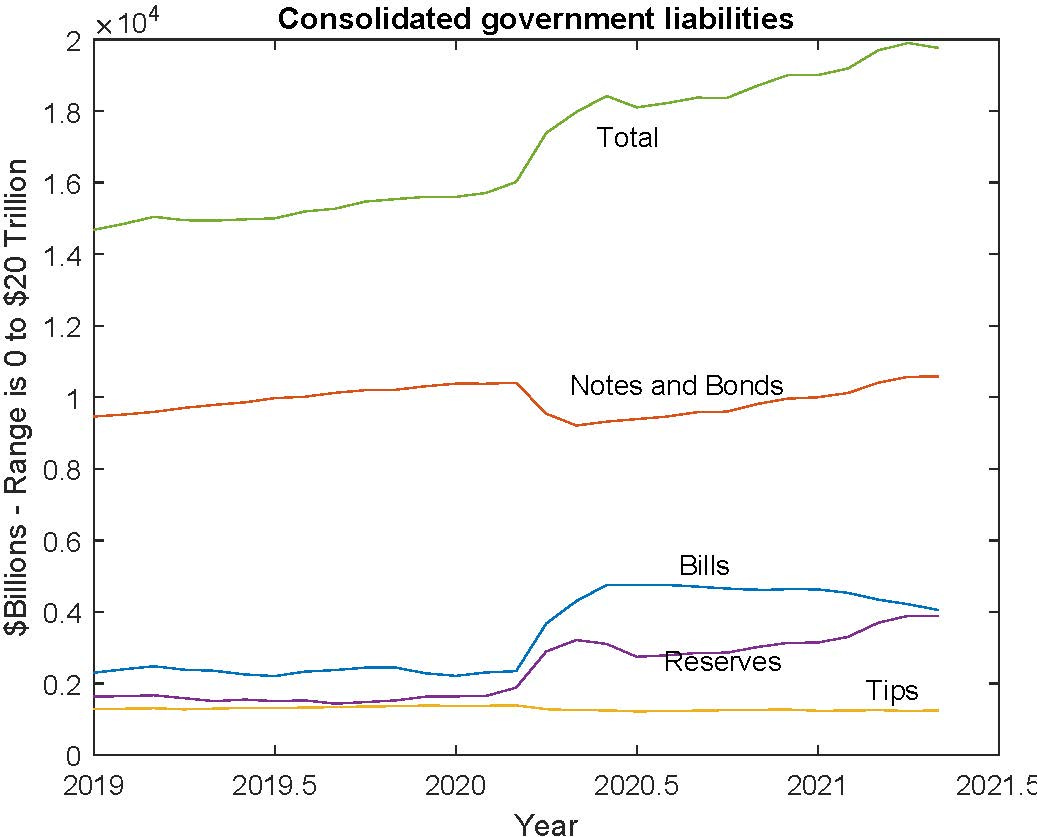

Ignoring the MBS part of the process, and focusing on consolidated government (Fed and Treasury) liabilities, here’s what’s happened since the beginning of 2019.

Figure 16

So, in debt management terms, Figure 16 is what we should care about (though there may be issues of on-the-run and off-the-run Treasuries to be concerned with) - it’s the net effect of Treasury and Fed actions that matters, not the Treasury securities held as assets by the Fed. In Figure 1, the total is Treasury notes and bonds plus Treasury bills, plus TIPS, plus reserves. All Treasury security quantities are what is held by the public, that is subtracting securities held by the Fed from securities issued by the Treasury. Notes and bonds are Treasuries with maturities greater than one year, and bills are T-bills, which have maturities of a year or less. The scale on the vertical axis runs from 0 to $20 trillion, so 1 is $10 trillion.

In Figure 16, note the runup in consolidated government debt during the pandemic. But given the collective actions of the Treasury and the Fed, notes and bonds are at about the level they were in early 2020, and bills and reserves have roughly doubled in both cases. It’s hard to see it in the picture, but TIPS have declined as a fraction of the total. In January 2019, bills and reserves accounted for 26.8% of consolidated government debt, notes and bonds for 64.4%, and TIPS for 8.8%. By May 2021, this had changed to 40.2% for bills and reserves, 53.5% for notes and bonds, and 6.3% for TIPS.

So, consolidated government debt is on average of shorter maturity, and much more of it is reserves locked in the banking system. In January 2019, 11.1% of consolidated government debt was reserves, and in May 2021 that number was 19.7%. The Fed claims that turning Treasuries and MBS into reserves is a good thing - it’s “accommodation,” apparently, and this should continue for a long time, according to the FOMC. But what’s actually going on here? The Fed is a financial intermediary that, like any financial intermediary, transforms assets. That’s it’s main function. But why are we supposed to be better off with less Treasuries and MBS in our possession, and more reserves loaded into the banking system?

To the extent that there is any science in debt management (and it seems this area is in need of much more economic research), one of the principles is serving the market. Debt managers spend time talking to financial market participants to find out what they want. More ten years? Fewer 3-month T-bills? So presumably the Treasury had something in mind when it issued the notes and bonds that the Fed is holding in its asset portfolio. Maybe the market participants who make use of 10-year Treasuries aren’t happy with the situation. Indeed, there are anecdotes about unhappy market participants in the midst of QE episodes. For example, in 2020 the Bank of Canada reduced its asset purchases from $5 billion per week to $4 billion. Though the Bank didn’t say so, that seems to have been a response to complaints from market participants about shortages of government debt.

Further, if you think about what’s going on currently, you may be suspicious that marginal asset purchases by the Fed are doing absolutely nothing. It seems that, roughly, each additional dollar of asset purchases shows up as an additional dollar of ON-RRP balances at the Fed, with reserves unchanged. So, at the margin, the Fed is converting long-maturity safe assets into repos. But any financial entity not subject to banking regulation can do that - the Fed has no natural advantage in that activity, so it should have no effect. It’s perhaps astonishing that the Fed has itself tied up in knots about when it is going to even talk about reducing the volume in an asset purchase program that is having no discernible effect.

As well, from our analysis above, it seems there are good reasons to doubt that reserves are a useful form of consolidated government debt, not only relative to T-bills, but relative to any maturity of Treasuries. Reserves are safe assets that can be held only by a closely regulated set of financial institutions, and those regulations mean that this is an inefficient use of safe consolidated government debt. The regulations are there for good reasons, and reserves are indeed useful for intraday transactions. But, as far as I can tell, overnight reserves serve no useful purpose that cannot be accomplished more efficiently with Treasury debt.